Every DBA has seen it at least once. You are looking at the production database and something feels wrong. CPU is climbing. Logical reads are surging. One or two sessions are consuming far more resources than everything else combined.

You drill down into the SQL.

The query is unfamiliar. It joins more tables than you would expect, sometimes even joining the same table multiple times. The execution plan is complex, the logical reads enormous.

The first question is always the same: where did this query come from?

Often the answer is simple. A new application feature has been released. Somewhere inside it is a query that looked perfectly reasonable in testing. Run once or twice, it behaved well enough.

Production tells a different story.

Now the query is executed repeatedly. Sometimes concurrently. Sometimes triggered by user behaviour the test harness never simulated. Occasionally the query runs long enough for the application to time out, so the user refreshes the page, launching another execution while the first one is still running.

What looked harmless in isolation becomes dangerous when multiplied across real workloads.

But a DBA usually has one advantage: you can usually find the human behind the query.

Someone wanted to know something. Once you understand that intent, the workload can usually be controlled. Run it less often. Move it elsewhere. Rewrite it entirely.

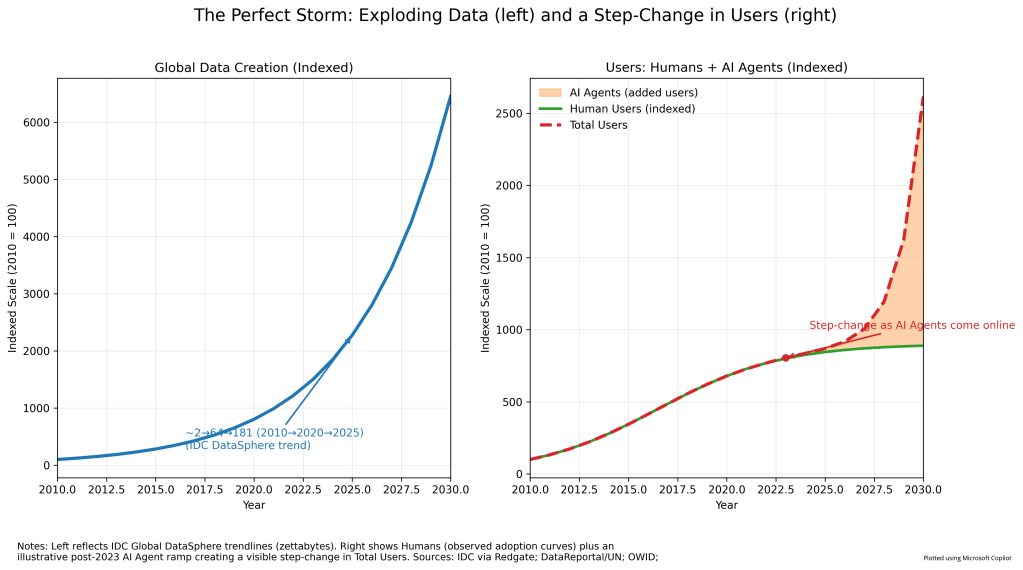

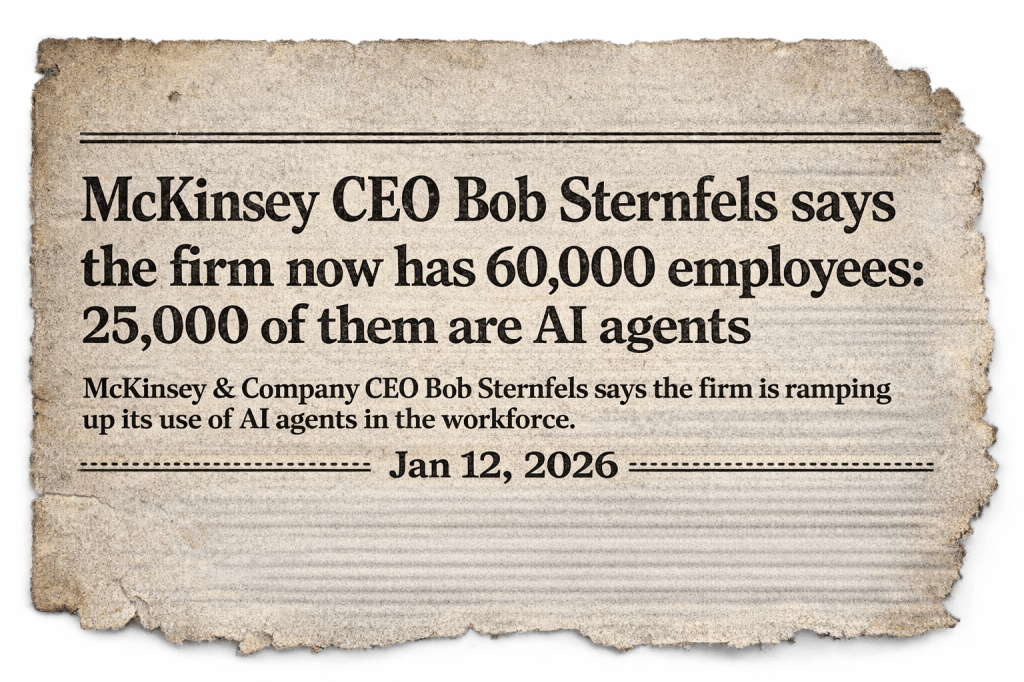

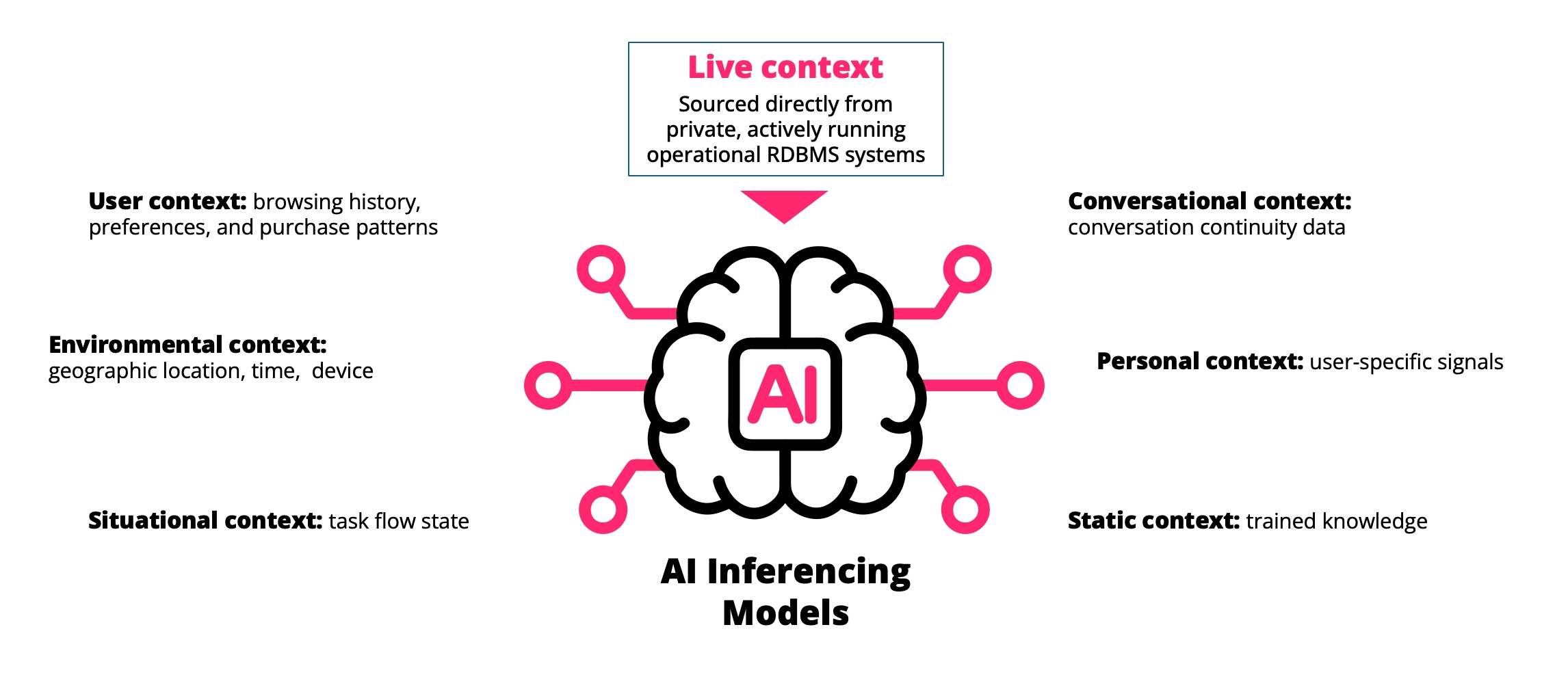

Operational databases survive because their workloads are ultimately bounded by human intent. AI agents change this equation in a subtle but important way.

When the Database Becomes Part of the Reasoning Process

Traditional enterprise applications interact with databases in predictable ways.

An application developer writes the query. It is tested, reviewed, and eventually deployed. Over time the database develops a recognisable workload pattern. DBAs learn those patterns, optimise them, and build operational safeguards around them.

Even complex systems ultimately follow this model. A user action triggers application logic, which triggers a known set of database queries.

AI agents behave differently.

Instead of executing a predefined query pattern, an agent may generate queries dynamically as part of a reasoning process. It retrieves data, evaluates the result, refines the question… and queries again.

In other words, the database is no longer simply answering a question. It becomes part of the mechanism the system uses to figure out the answer.

This subtle shift has an important consequence.

Applications constrain database workloads.

Agents amplify them.

The Amplification Effect

A traditional application might translate a single user action into one or two database queries.

An agent may translate the same request into many.

The agent retrieves information, evaluates it, and then decides what to ask next. It may retry a query with different parameters, join additional tables, or explore alternative paths through the data.

Some systems do this only once or twice. More autonomous agents may repeat the process multiple times in a reasoning loop.

From the database’s perspective, a single human question can now generate many queries. In simple retrieval pipelines this may only be a handful. In more autonomous reasoning systems it can grow to dozens — sometimes even hundreds — as the agent explores the data.

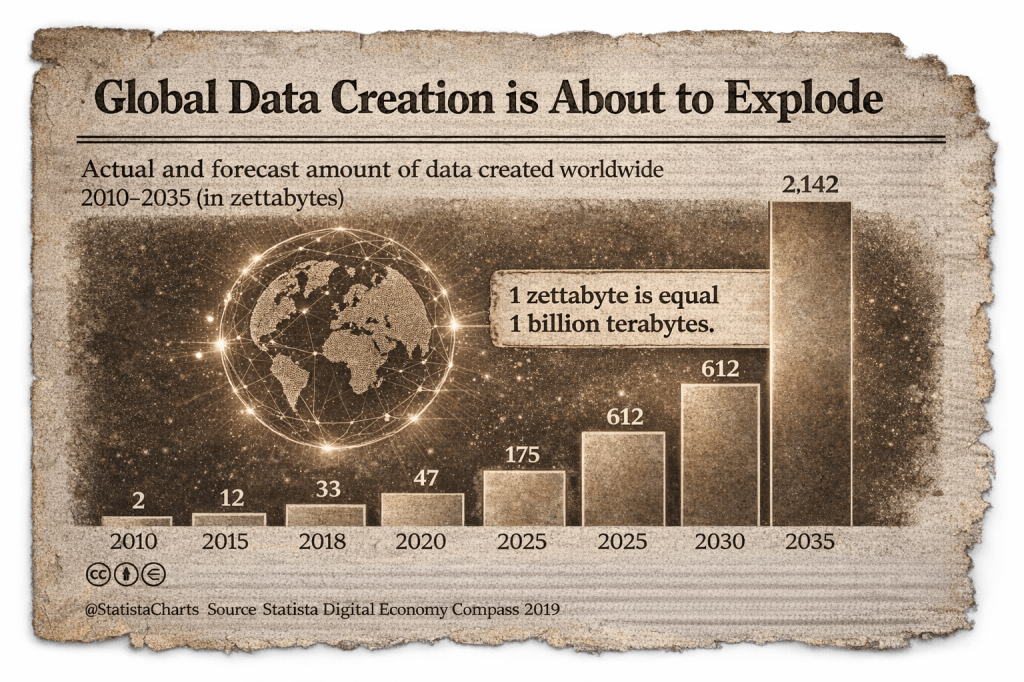

Multiply that pattern across thousands of employees interacting with AI systems, and the database workload begins to look very different from the one the system was originally designed to support.

This is not necessarily a flaw. It is simply how exploratory systems behave. But it does change the shape of the workload interacting with production systems.

Why Traditional Controls Are Not Enough

Experienced DBAs will recognise that production databases already include many mechanisms designed to control runaway workloads.

Connection limits, query governors, resource groups, and timeouts exist precisely because poorly behaved queries can destabilise shared systems.

These controls work well when applications generate predictable query patterns.

What they are less suited to is a workload whose shape is not known in advance.

Agentic systems can generate new queries dynamically, retry failed steps, or explore alternative reasoning paths. The individual queries may not be problematic on their own. The challenge is the emergent behaviour that appears when many such queries interact with a production workload.

The result is a new class of operational uncertainty. In practice this can manifest as unexpected infrastructure consumption, runaway query costs in cloud databases, or production incidents triggered by exploratory workloads interacting badly with operational traffic.

When a traditional query misbehaves, a DBA can usually trace it back to a specific application feature or report. With agentic systems, the activity observed in the database may simply be a side effect of an evolving reasoning process.

Understanding why a query is running becomes much harder.

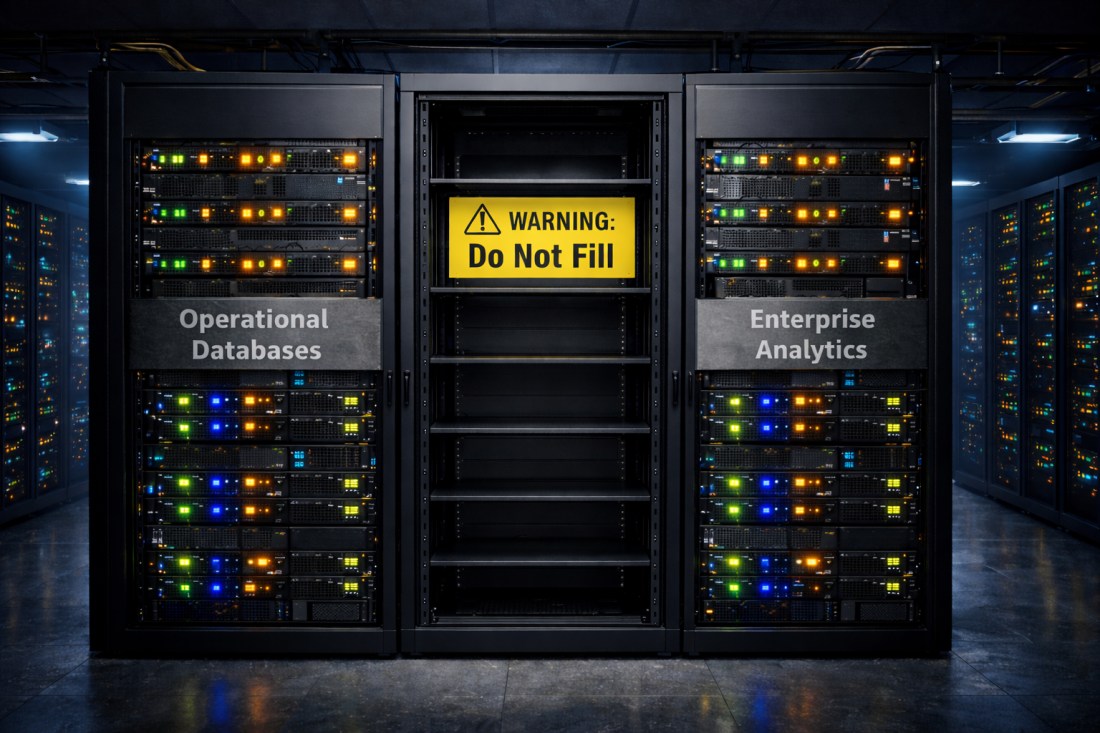

Enterprise Architectures Will Evolve

For this reason, the architecture implied by many early AI demonstrations is unlikely to survive unchanged in large enterprise environments.

Those demonstrations often show AI agents querying operational databases directly. For simple scenarios, that approach works well enough.

At scale, however, exploratory workloads interacting directly with systems of record create operational and economic pressures that are difficult to manage.

The likely response is architectural evolution.

Instead of allowing agents to query operational systems directly, enterprises will increasingly introduce intermediate layers designed to absorb exploratory behaviour. These layers might include analytical replicas, semantic data services, curated retrieval surfaces, vector indexes, materialised views, or other forms of controlled query infrastructure.

What matters is not the specific technology. It is the architectural separation.

Systems of record remain the authoritative source of enterprise data. But the exploratory behaviour of AI agents will increasingly occur one step removed from those systems.

Until architectures evolve to contain that behaviour, many enterprise AI initiatives will struggle to deliver the level of return on investment that early demonstrations appear to promise.

Not because the models fail, but because the surrounding architecture has not yet caught up with how those models actually behave.

This article is part of the Databases in the Age of AI series.