Storage for DBAs: Data deduplication – or “dedupe” – is a technology which falls under the umbrella of data reduction, i.e. reducing the amount of capacity required to store data. In very simple terms it involves looking for repeating patterns and replacing them with a marker: as long as the marker requires less space than the pattern it replaces, you have achieved a reduction in capacity. Deduplication can happen anywhere: on storage, in memory, over networks, even in database design – for example, the standard database star or snowflake schema. However, in this article we’re going to stick to talking about dedupe on storage, because this is where I believe there is a myth that needs debunking: databases are not a great use case for dedupe.

Deduplication Basics: Inline or Post-Process

If you are using data deduplication either through a storage platform or via software on the host layer, you have two basic choices: you can deduplicate it at the time that it is written (known as inline dedupe) or allow it to arrive and then dedupe it at your leisure in some transparent manner (known as post-process dedupe). Inline dedupe affects the time taken to complete every write, directly affecting I/O performance. The benefit of post-process dedupe therefore appears to be that it does not affect performance – but think again: post-process dedupe first requires data to be written to storage, then read back out into the dedupe algorithm, before being written to storage again in its deduped format – thus magnifying the amount of I/O traffic and indirectly affecting I/O performance. In addition, post-process dedupe requires more available capacity to provide room for staging the inbound data prior to dedupe.

If you are using data deduplication either through a storage platform or via software on the host layer, you have two basic choices: you can deduplicate it at the time that it is written (known as inline dedupe) or allow it to arrive and then dedupe it at your leisure in some transparent manner (known as post-process dedupe). Inline dedupe affects the time taken to complete every write, directly affecting I/O performance. The benefit of post-process dedupe therefore appears to be that it does not affect performance – but think again: post-process dedupe first requires data to be written to storage, then read back out into the dedupe algorithm, before being written to storage again in its deduped format – thus magnifying the amount of I/O traffic and indirectly affecting I/O performance. In addition, post-process dedupe requires more available capacity to provide room for staging the inbound data prior to dedupe.

Deduplication Basics: (Block) Size Matters

In most storage systems dedupe takes place at a defined block size, whereby each block is hashed to produce a unique key before being compared with a master lookup table containing all known hash keys. If the newly-generated key already exists in the lookup table, the block is a duplicate and does not need to be stored again. The block size is therefore pretty important, because the smaller the granularity, the higher the chances of finding a duplicate:

In the picture you can see that the pattern “1234”repeats twice over a total of 16 digits. With an 8-digit block size (the lower line) this repeat is not picked up, since the second half of the 8-digit pattern does not repeat. However, by reducing the block size to 4 digits (the upper line) we can now get a match on our unique key, meaning that the “1234” pattern only needs to be stored once.

In the picture you can see that the pattern “1234”repeats twice over a total of 16 digits. With an 8-digit block size (the lower line) this repeat is not picked up, since the second half of the 8-digit pattern does not repeat. However, by reducing the block size to 4 digits (the upper line) we can now get a match on our unique key, meaning that the “1234” pattern only needs to be stored once.

This sounds like great news, let’s just choose a really small block size, right? But no, nothing comes without a price – and in this case the price comes in the size of the hashing lookup table. This table, which contains one key for every unique block, must range in size from containing just one entry (the “ideal” scenario where all data is duplicated) to having one entry for each block (the worst case scenario where every block is unique). By making the block size smaller, we are inversely increasing the maximum size of the hashing table: half the block size means double the potential number of hash entries.

Hash Abuse

Why do we care about having more hash entries? There are a few reasons. First there is the additional storage overhead: if your data is relatively free of duplication (or the block size does not allow duplicates to be detected) then not only will you fail to reclaim any space but you may end up using extra space to store all of the unique keys associated with each block. This is clearly not a great outcome when using a technology designed to reduce the footprint of your data.  Secondly, the more hash entries you have, the more entries you need to scan through when comparing freshly-hashed blocks during writes or locating existing blocks during reads. In other words, the more of a performance overhead you will suffer in order to read your data and (in the case of inline dedupe) write it.

Secondly, the more hash entries you have, the more entries you need to scan through when comparing freshly-hashed blocks during writes or locating existing blocks during reads. In other words, the more of a performance overhead you will suffer in order to read your data and (in the case of inline dedupe) write it.

If this is sounding familiar to you, it’s because the hash data is effectively a database in which storage metadata is stored and retrieved. Just like any database the performance will be dictated by the volume of data as well as the compute resource used to manipulate it, which is why many vendors choose to store this metadata in DRAM. Keeping the data in memory brings certain performance benefits, but with the price of volatility: changes in memory will be lost if the power is interrupted, so regular checkpoints are required to persistent storage. Even then, battery backup is often required, because the loss of even one hash key means data corruption. If you are going to replace your data with markers from a lookup table, you absolutely cannot afford to lose that lookup table, or there will be no coming back.

Database Deduplication – Don’t Be Duped

Now that we know what dedupe is all about, let’s attempt to apply it to databases and see what happens. You may be considering the use of dedupe technology with a database system, or you may simply be considering the use of one of a number of recent storage products that have inline dedupe in place as an “always on” option, i.e. you cannot turn it off regardless of whether it helps or hinders. The vendor may make all sorts of claims about the possibilities of dedupe, but how much benefit will you actually see?

Let’s consider the different components of a database environment in the context of duplication:

- Oracle datafiles contain data blocks which have block headers at the start of the block. These contain numbers which are unique for each datafile, making deduplication impossible at the database block size. In addition, the end of each block contains a tailcheck section which features a number generated using data such as the SCN, so even if the block were divided into two the second half would offer limited opportunity for dedupe while the first half would offer none.

- Even if you were able to break down Oracle blocks into small enough chunks to make dedupe realistic, any duplication of data is really a massive warning about your database design: normalise your data! Also, consider features like index key compression which are part of the Enterprise Edition license.

- Most Oracle installations have multiplexed copies of important files like online redo logs and controlfiles. These files are so important that Oracle synchronously maintains multiple copies in order to ensure against data loss. If your storage system is deduplicating these copies, this is a bad thing – particularly if it’s an always on feature that gives you no option.

- While unallocated space (e.g. in an ASM diskgroup) might appear to offer the potential for dedupe, this is actually a problem which you should solve using another storage technology: thin provisioning.

- You may have copies of datafiles residing on the same storage as production, which therefore allow large-scale deduplication to take place; perhaps they are used as backups or test/development environments. However, in the latter case, test/dev environments are a use case for space-efficient snapshots rather than dedupe. And if you are keeping your backups on the same storage system as your production data, well… good luck to you. There is nothing more for you here.

- Maybe we aren’t talking about production data at all. You have a large storage array which contains multiple copies of your database for use with test/dev environments – and thus large portions of the data are duplicated. Bingo! The perfect use case for storage dedupe, right? Wrong. Database-level problems require database-level solutions, not storage-level workarounds. Get yourself some licenses for Delphix and you won’t look back.

To conclude, while dedupe is great in use cases like VDI, it offers very limited benefit in database environments while potentially making performance worse. That in itself is worrying, but what I really see as a problem is the way that certain storage vendors appear to be selling their capacity based on assumed levels of dedupe, i.e. “Sure we are only giving you X terabytes of storage for Y price, but actually you’ll get 10:1 dedupe which means the price is really ten times lower!”

To conclude, while dedupe is great in use cases like VDI, it offers very limited benefit in database environments while potentially making performance worse. That in itself is worrying, but what I really see as a problem is the way that certain storage vendors appear to be selling their capacity based on assumed levels of dedupe, i.e. “Sure we are only giving you X terabytes of storage for Y price, but actually you’ll get 10:1 dedupe which means the price is really ten times lower!”

Sizing should be based on facts, not assumptions. Just like in the real world, nothings comes for free in I.T. – and we’ve all learnt that the hard way at some point. Don’t be duped.

Storage for DBAs: The strange thing about enterprise databases is that the people who design, manage and support them are often disassociated from the people who pay the bills. In fact, that’s not unusual in enterprise IT, particularly in larger organisations where purchasing departments are often at opposite ends of the org chart to operations and engineering staff.

Storage for DBAs: The strange thing about enterprise databases is that the people who design, manage and support them are often disassociated from the people who pay the bills. In fact, that’s not unusual in enterprise IT, particularly in larger organisations where purchasing departments are often at opposite ends of the org chart to operations and engineering staff.

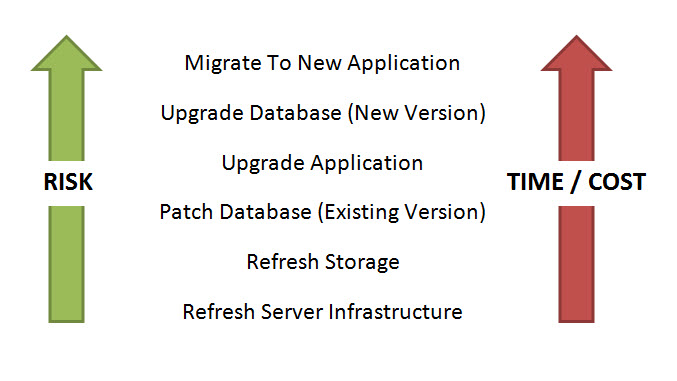

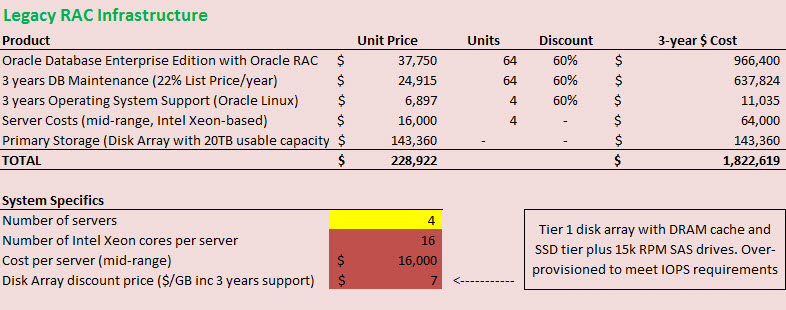

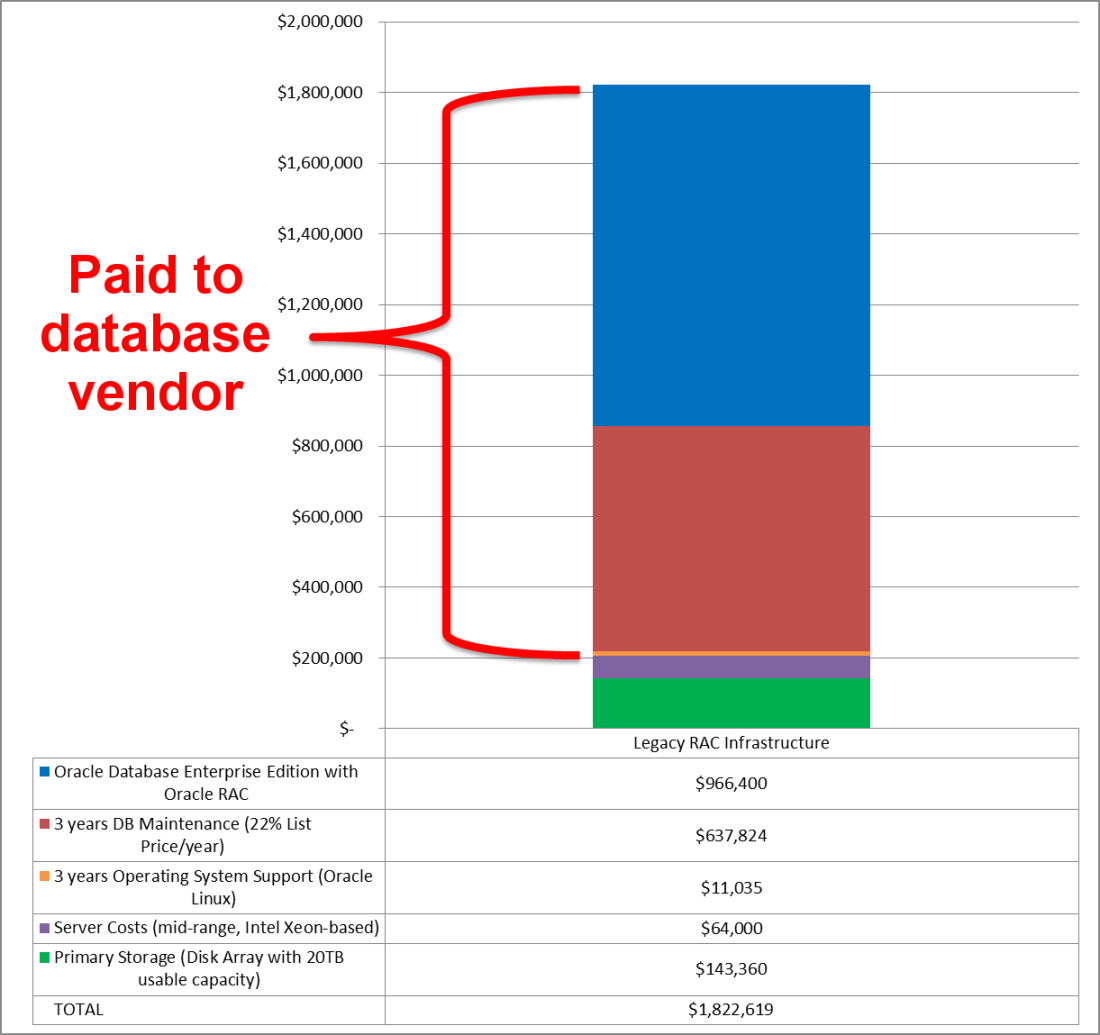

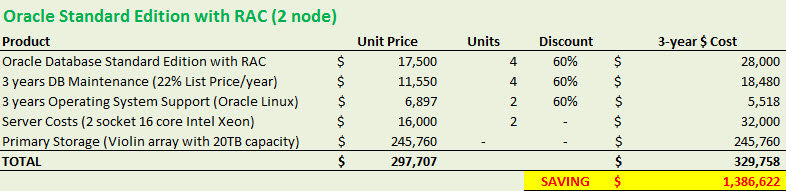

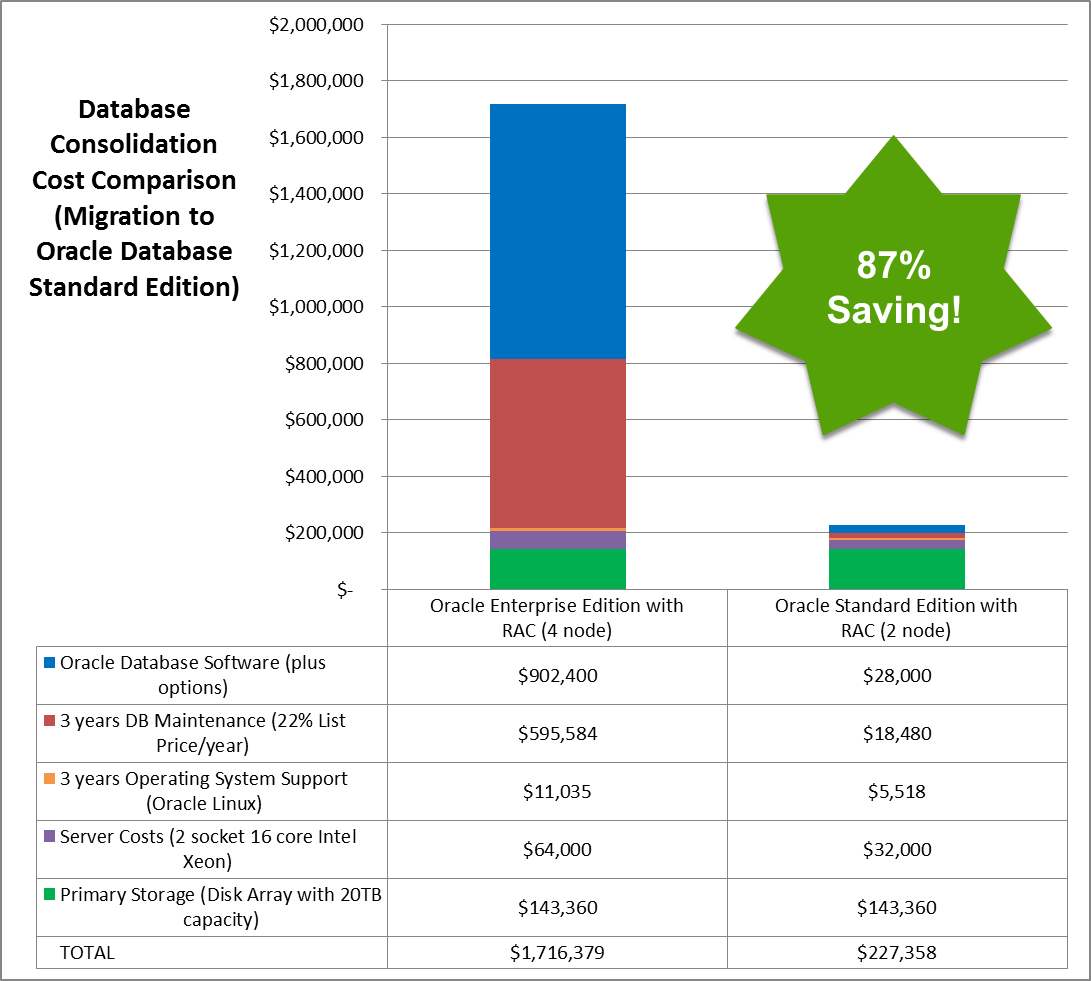

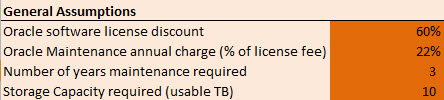

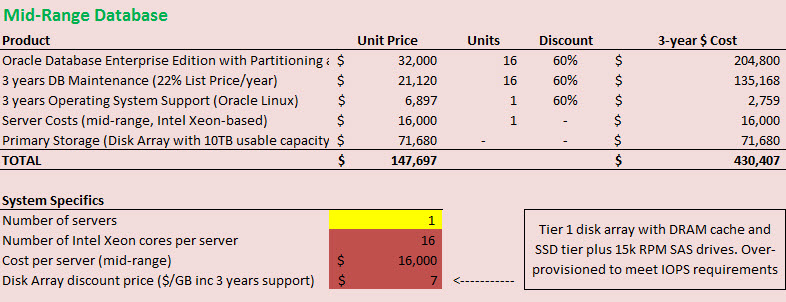

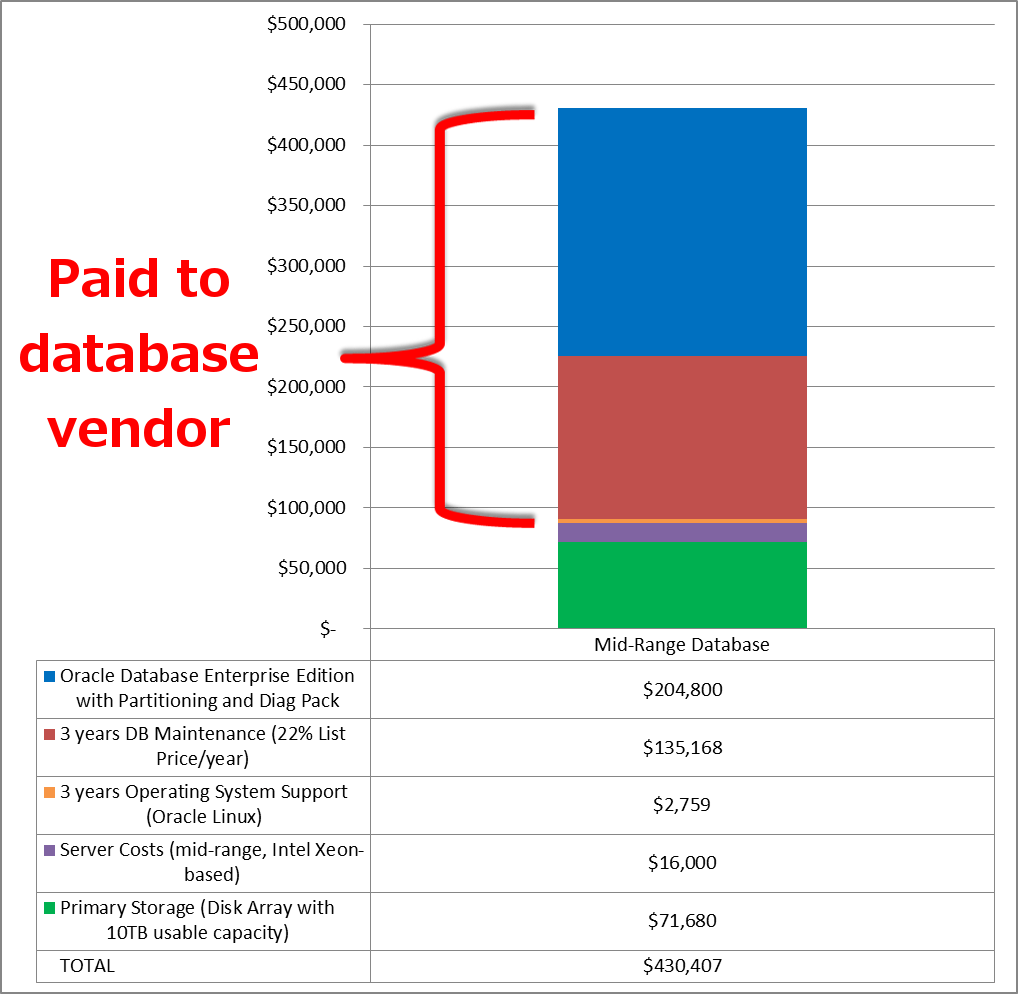

There are two points I want to make here. One is that the cost of storage is often relatively small in terms of the total cost. If a large amount of money is being spent on licensing the environment it makes sense to ensure that the storage enables better performance, i.e. results in a better return on investment.

There are two points I want to make here. One is that the cost of storage is often relatively small in terms of the total cost. If a large amount of money is being spent on licensing the environment it makes sense to ensure that the storage enables better performance, i.e. results in a better return on investment.

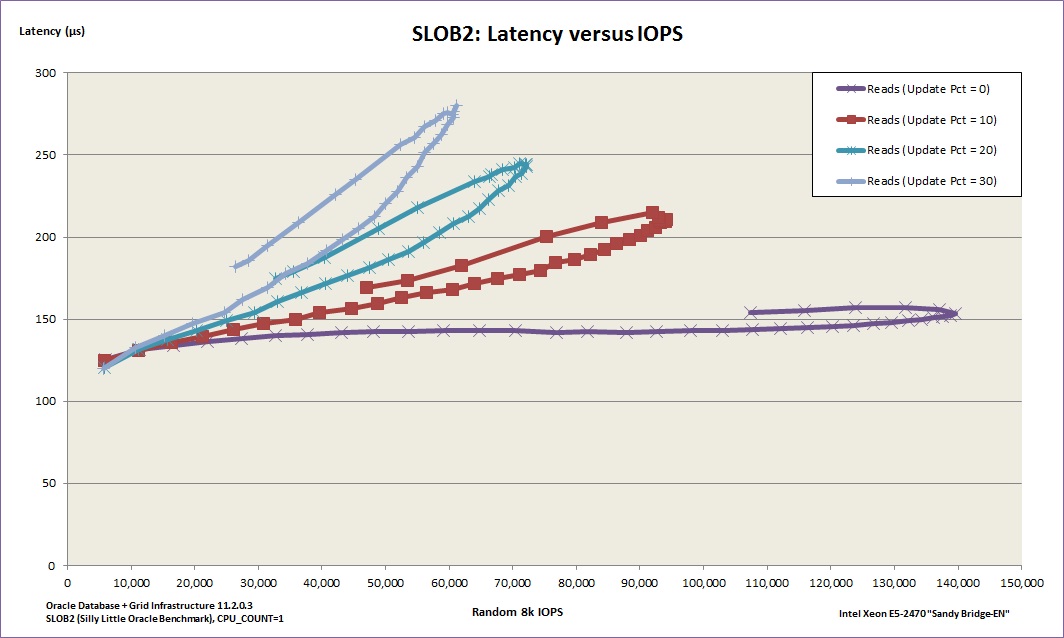

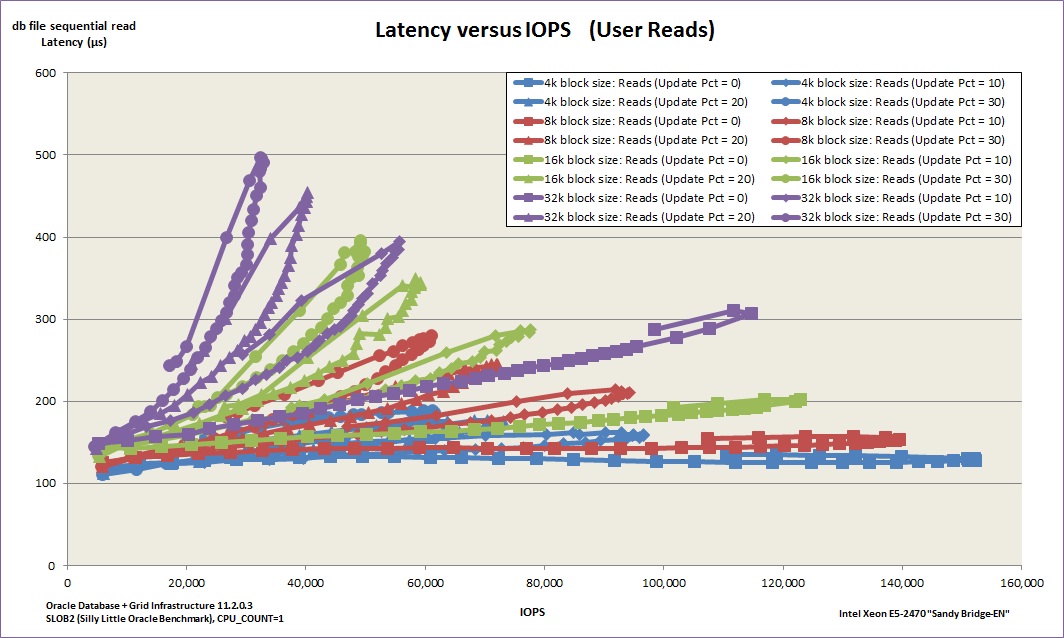

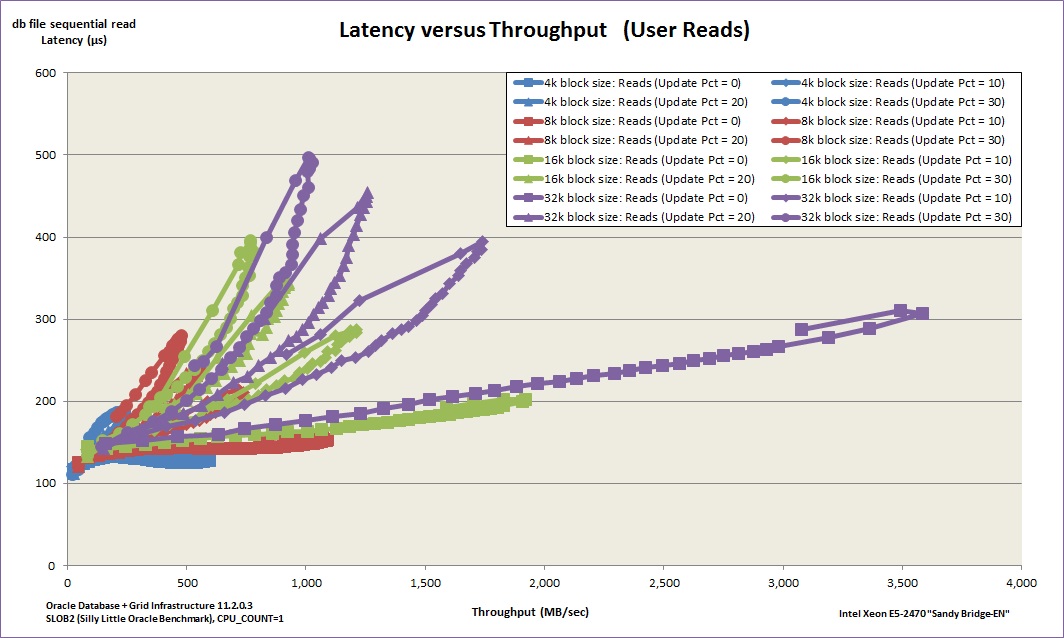

Forget everything else. Latency is the critical factor because this is what injects delay into your system. Latency means lost time; time that could have been spent busily producing results, but is instead spent waiting for I/O resources.

Forget everything else. Latency is the critical factor because this is what injects delay into your system. Latency means lost time; time that could have been spent busily producing results, but is instead spent waiting for I/O resources.

Short post to point out that I’ve now posted the updated

Short post to point out that I’ve now posted the updated