In the first part of this blog series on In Memory Databases (IMDBs) I talked about the definition of “memory” and found it surprisingly hard to pin down. There was no doubt that Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM), such as that found in most modern computers, fell into the category of memory whilst disk clearly did not. The medium which caused the problem was NAND flash memory, such as that found in consumer devices like smart phones, tablets and USB sticks or enterprise storage like the flash memory arrays made by my employer Violin Memory.

In the first part of this blog series on In Memory Databases (IMDBs) I talked about the definition of “memory” and found it surprisingly hard to pin down. There was no doubt that Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM), such as that found in most modern computers, fell into the category of memory whilst disk clearly did not. The medium which caused the problem was NAND flash memory, such as that found in consumer devices like smart phones, tablets and USB sticks or enterprise storage like the flash memory arrays made by my employer Violin Memory.

There is no doubt in my mind that flash memory is a type of memory – otherwise we would have to have a good think about the way it was named. My doubts are along different lines: if a database is running on flash memory, can it be described as an IMDB? After all, if the answer is yes then any database running on Violin Memory is an In Memory Database, right?

What Is An In Memory Database?

As always let’s start with the stupid questions. What does an IMDB do that a non-IMDB database does not do? If I install a regular Oracle database (for example) it will have a System Global Area (SGA) and a Program Global Area (PGA), both of which are areas set aside in volatile DRAM in order to contain cached copies of data blocks, SQL cursors and sorting or hashing areas. Surely that’s “in-memory” in anyone’s definition? So what is the difference between that and, for example, Oracle TimesTen or SAP HANA?

Let’s see if the Oracle TimesTen documentation can help us:

“Oracle TimesTen In-Memory Database operates on databases that fit entirely in physical memory”

That’s a good start. So with an IMDB, the whole dataset fits entirely in physical memory. I’m going to take that sentence and call it the first of our fundamental statements about IMDBs:

IMDB Fundamental Requirement #1:

IMDB Fundamental Requirement #1:

In Memory Databases fit entirely in physical memory.

But if I go back to my Oracle database and ensure that all of the data fits into the buffer cache, surely that is now an In Memory Database?

Maybe an IMDB is one which has no physical files? Of course that cannot be true, because memory is (or can be) volatile, so some sort of persistent later is required if the data is to be retained in the event of a power loss. Just like a “normal” database, IMDBs still have to have datafiles and transaction logs located on persistent storage somewhere (both TimesTen and SAP HANA have checkpoint and transaction logs located on filesystems).

So hold on, I’m getting dangerously close to the conclusion that an IMDB is simply a normal DB which cannot grow beyond the size of the chunk of memory it has been allocated. What’s the big deal, why would I want that over say a standard RDBMS?

Why is an In-Memory Database Fast?

Actually that question is not complete, but long questions do not make good section headers. The question really is: why is an In Memory Database faster than a standard database whose dataset is entirely located in memory?

Back to our new friend the Oracle TimesTen documentation, with the perfectly-entitled section “Why is Oracle TimesTen In-Memory Database fast?“:

“Even when a disk-based RDBMS has been configured to hold all of its data in main memory, its performance is hobbled by assumptions of disk-based data residency. These assumptions cannot be easily reversed because they are hard-coded in processing logic, indexing schemes, and data access mechanisms.

TimesTen is designed with the knowledge that data resides in main memory and can take more direct routes to data, reducing the length of the code path and simplifying algorithms and structure.”

This is more like it. So an IMDB is faster than a non-IMDB because there is less code necessary to manipulate data. I can buy into that idea. Let’s call that the second fundamental statement about IMDBs:

IMDB Fundamental Requirement #2:

IMDB Fundamental Requirement #2:

In Memory Databases are fast because they do not have complex code paths for dealing with data located on storage.

I think this is probably a sufficient definition for an IMDB now. So next let’s have a look at the different implementations of “IMDBs” available today and the claims made by the vendors.

Is My Database An In Memory Database?

Any vendor can claim to have a database which runs in memory, but how many can claim that theirs is an In Memory Database? Let’s have a look at some candidates and subject them to analysis against our IMDB fundamentals.

1. Database Running in DRAM – e.g. SAP HANA

I have no experience of Oracle TimesTen but I have been working with SAP HANA recently so I’m picking that as the example. In my opinion, HANA (or NewDB as it was previously known) is a very exciting database product – not especially because of the In Memory claims, but because it was written from the ground up in an effort to ignore previous assumptions of how an RDBMS should work. In contrast, alternative RDBMS such as Oracle, SQL Server and DB/2 have been around for decades and were designed with assumptions which may no longer be true – the obvious one being that storage runs at the speed of disk.

I have no experience of Oracle TimesTen but I have been working with SAP HANA recently so I’m picking that as the example. In my opinion, HANA (or NewDB as it was previously known) is a very exciting database product – not especially because of the In Memory claims, but because it was written from the ground up in an effort to ignore previous assumptions of how an RDBMS should work. In contrast, alternative RDBMS such as Oracle, SQL Server and DB/2 have been around for decades and were designed with assumptions which may no longer be true – the obvious one being that storage runs at the speed of disk.

The HANA database runs entirely in DRAM on Intel x86 processors running SUSE Linux. It has a persistent layer on storage (using a filesystem) for checkpoint and transaction logs, but all data is stored in DRAM along with an additional allocation of memory for hashing, sorting and other work area stuff. There are no code paths intended to decide if a data block is in memory or on disk because all data is in memory. Does HANA meet our definition of an IMDB? Absolutely.

What are the challenges for databases running in DRAM? One of the main ones is scalability. If you impose a restriction that all data must be located in DRAM then the amount of DRAM available is clearly going to be important. Adding more DRAM to a server is far more intrusive than adding more storage, plus servers only have a limited number of locations on the system bus where additional memory can be attached. Price is important, because DRAM is far more expensive than storage media such as disk or flash. High Availability is also a key consideration, because data stored in memory will be lost when the power goes off. Since DRAM cannot be shared amongst servers in the same way as networked storage, any multiple-node high availability solution has to have some sort of cache coherence software in place, which increases the complexity and moves the IMDB away from the goal of IMDB Fundamental #2.

Gong back to HANA, SAP have implemented the ability to scale up (adding more DRAM – despite Larry’s claims to the contrary, you can already buy a 100TB HANA database system from IBM) as well as to scale out by adding multiple nodes to form a cluster. It is going to be fascinating to see how the Oracle vs SAP HANA battle unfolds. At the moment 70% of SAP customers are running on Oracle – I would expect this number to fall significantly over the next few years.

2. Database Running on Flash Memory – e.g. on Violin Memory

Now this could be any database, from Oracle through SQL Server to PostgreSQL. It doesn’t have to be Violin Memory flash either, but this is my blog so I get to choose. The point is that we are talking about a database product which keeps data on storage as well as in memory, therefore requiring more complex code paths to locate and manage that data.

Now this could be any database, from Oracle through SQL Server to PostgreSQL. It doesn’t have to be Violin Memory flash either, but this is my blog so I get to choose. The point is that we are talking about a database product which keeps data on storage as well as in memory, therefore requiring more complex code paths to locate and manage that data.

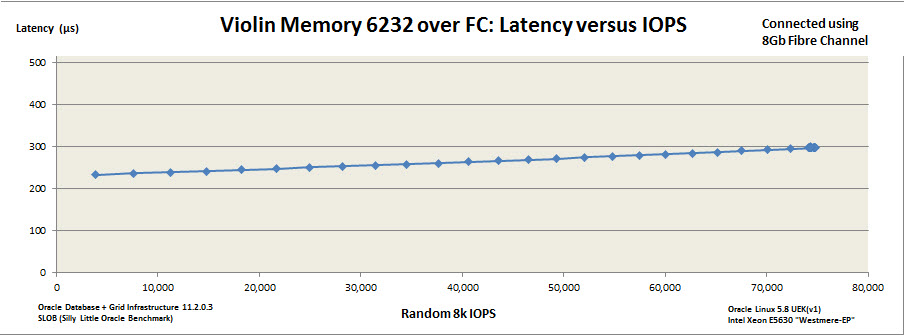

The use of flash memory means that storage access times are many orders of magnitude faster than disk, resulting in exceptional performance. Take a look at recent server benchmark results and you will see that Cisco, Oracle, IBM, HP and VMware have all been using Violin Memory flash memory arrays to set new records. This is fast stuff. But does a (normal) database running on flash memory meet our fundamental requirements to make it an IMDB?

First there is the idea of whether it is “memory”. As we saw before this is not such a simple question to answer. Some of us (I’m looking at you Kevin) would argue that if you cannot use memory functions to access and manipulate it then it is not memory. Others might argue that flash is a type of memory accessed using storage protocols in order to gain the advantages that come with shared storage, such as redundancy, resilience and high availability.

Luckily the whole question is irrelevant because of our second fundamental requirement, which is that the database software does not have complex code paths for dealing with blocks located on storage. Bingo. So running an Oracle database on flash memory does not make it an In Memory Database, it just makes it a database which runs at the speed of flash memory. That’s no bad thing – the main idea behind the creation of IMDBs was to remove the bottlenecks created by disk, so running at the speed of flash is a massive enhancement (hence those benchmarks). But using our definitions above, Oracle on flash does not equal IMDB.

On the other hand, running HANA or some other IMDB on flash memory clearly has some extra benefits because the checkpoint and transactional logs will be less of a bottleneck if they write data to flash than if they were writing to disk. So in summary, the use of flash is not the key issue, it’s the way the database software is written that makes the difference.

3. Database Accessing Remote DRAM and Flash Memory: Oracle Exadata X3

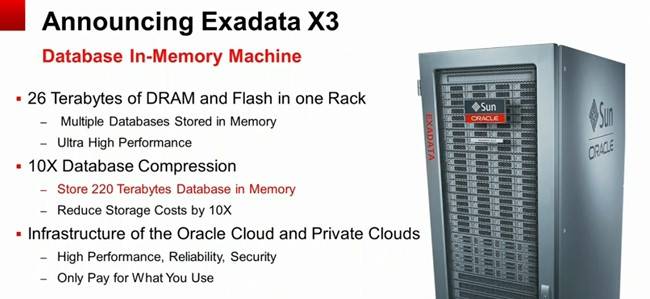

Why am I talking about Oracle Exadata now? Because at the recent Oracle OpenWorld a new version of Exadata was announced, with a new name: the Oracle Exadata X3 Database In-Memory Machine. Regular readers of my blog will know that I like to keep track of Oracle’s rebranding schemes to monitor how the Exadata product is being marketed, and this is yet another significant renaming of the product.

Why am I talking about Oracle Exadata now? Because at the recent Oracle OpenWorld a new version of Exadata was announced, with a new name: the Oracle Exadata X3 Database In-Memory Machine. Regular readers of my blog will know that I like to keep track of Oracle’s rebranding schemes to monitor how the Exadata product is being marketed, and this is yet another significant renaming of the product.

According to the press release, “[Exadata] can store up to hundreds of Terabytes of compressed user data in Flash and RAM memory, virtually eliminating the performance overhead of reads and writes to slow disk drives“. Now that’s a brave claim, although to be fair Oracle is at least acknowledging that this is “Flash and RAM memory”. On the other hand, what’s this about “hundreds of Terabytes of compressed user data”? Here’s the slide from the announcement, with the important bit helpfully highlighted in red (by Oracle not me):

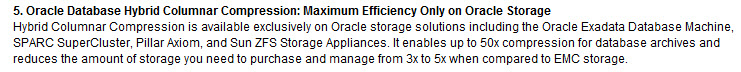

Also note the “26 Terabytes of DRAM and Flash in one Rack” line. Where is that DRAM and Flash? After all, each database server in an Exadata X3-2 has only 128GB DRAM (upgradeable to 256GB) and zero flash. The answer is that it’s on the storage grid, with each storage cell (there are 14 in a full rack) containing 1.6TB flash and 64GB DRAM. But the database servers cannot directly address this as physical memory or block storage. It is remote memory, accessed over Infiniband with all the overhead of IPC, iDB, RDS and Infiniband ZDP. Does this make Exadata X3 an In Memory Database?

I don’t see how it can. The first of our fundamental requirements was that the database should fit entirely in memory. Exadata X3 does not meet this requirement, because data is still stored on disk. The DRAM and Flash in the storage cells are only levels of cache – at no point will you have your entire dataset contained only in the DRAM and Flash*, otherwise it would be pretty pointless paying for the 168 disks in a full rack – even more so because Oracle Exadata Storage Licenses are required on a per disk basis, so if you weren’t using those disks you’d feel pretty hard done by.

[*see comments section below for corrections to this statement]

But let’s forget about that for a minute and turn our attention to the second fundamental requirement, which is that the database is fast because it does not have complex code paths designed to manage data located both in memory or on disk. The press release for Exadata X3 says:

“The Oracle Exadata X3 Database In-Memory Machine implements a mass memory hierarchy that automatically moves all active data into Flash and RAM memory, while keeping less active data on low-cost disks”

This is more complexity… more code paths to handle data, not less. Exadata is managing data based on its usage rate, moving it around in multiple different levels of memory and storage (local DRAM, remote DRAM, remote flash and remote disks). Most of this memory and storage is remote to the database processes representing the end users and thus it incurs network and communication overheads. What’s more, to compound that story, the slide up above is talking about compressed data, so that now has to be uncompressed before being made available to the end user, navigating additional code paths and incurring further overhead. If you then add the even more complicated code associated with Oracle RAC (my feelings on which can be found here) the result is a multi-layered nest of software complexity which stores data in many different places.

Draw your own conclusions, but in my opinion Exadata X3 does not meet either of our requirements to be defined as an In Memory Database.

Conclusion

“In Memory” is a buzzword which can be used to describe a multitude of technologies, some of which fit the description better than others. Flash memory is a type of memory, but it is also still storage – whereas DRAM is memory accessed directly by the CPU. I’m perfectly happy calling flash memory a type of “memory”, even referring to it performing “at the speed of memory” as opposed to the speed of disk, but I cannot stretch to describing databases running on flash as “In Memory Databases”, because I believe that the only In Memory Databases are the ones which have been designed and written to be IMDBs from the ground up.

“In Memory” is a buzzword which can be used to describe a multitude of technologies, some of which fit the description better than others. Flash memory is a type of memory, but it is also still storage – whereas DRAM is memory accessed directly by the CPU. I’m perfectly happy calling flash memory a type of “memory”, even referring to it performing “at the speed of memory” as opposed to the speed of disk, but I cannot stretch to describing databases running on flash as “In Memory Databases”, because I believe that the only In Memory Databases are the ones which have been designed and written to be IMDBs from the ground up.

Anything else is just marketing…

Finally we come to CPU utilisation. It seems obvious that if you take all of your database environments and consolidate them onto one platform you will need a lot of CPU power to ensure they all coexist peacefully. This is where you really want to be able to overcommit, because CPUs are expensive. Maybe not as hardware components (although they certainly aren’t cheap), but as the major contributor to license cost. Oracle licenses most of its database software by the core, with a “multiplication factor” applied

Finally we come to CPU utilisation. It seems obvious that if you take all of your database environments and consolidate them onto one platform you will need a lot of CPU power to ensure they all coexist peacefully. This is where you really want to be able to overcommit, because CPUs are expensive. Maybe not as hardware components (although they certainly aren’t cheap), but as the major contributor to license cost. Oracle licenses most of its database software by the core, with a “multiplication factor” applied