Storage for DBAs: Do you want to sell your house? Or your car? Let’s go with the car – just indulge me on this one. You have a car, which you weren’t especially planning on selling, but I’m making you an offer you can’t refuse. I’m offering you one million dollars so how can you say no?

The only thing is, when we come to make the trade I turn up not with a suitcase full of cash but a single Mega Millions lottery ticket. How would you feel about that? You may well feel aggrieved that I am offering you something which cost me just $1 but my response is this: it has an effective value of well over $1m. Does that work for you?

Blurred Lines

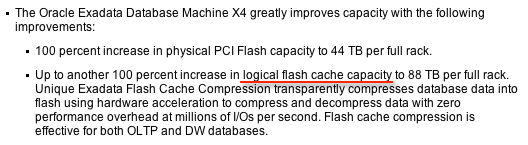

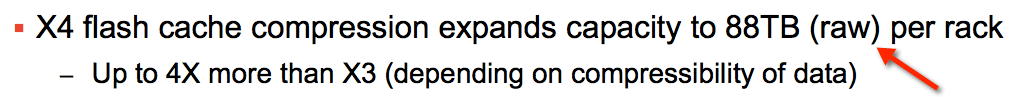

The thing is, this happens all the time in product marketing and we just put up with it. Oracle’s new Exadata Database Machine X4-2 has 44.8TB of raw flash in a full rack configuration, yet the datasheet states it has an effective flash capacity of 448TB. Excuse me? Let’s read the small print to find out what this means: apparently this is “the size of the data files that can often be stored in Exadata and be accessed at the speed of flash memory“. No guarantees then, you just might get that, if you’re lucky. I thought datasheets where supposed to be about facts?

Meanwhile, back in storageland, a look at some of the datasheets from various flash array vendors throws up a similar practice. One vendor shows the following flash capacity figures for their array:

- 2.75 – 11 TBs raw capacity

- 5 – 50 TBs effective capacity

In my last two posts I covered deduplication and data compression as part of an overall data reduction strategy in storage. To recap, I gave my opinion that dedupe has no place with databases (although it has major benefits in workloads such as VDI) while data compression has benefits but is not necessarily best implemented at the storage level.

Here’s the thing. Your database vendor’s software has options that allow you to perform data reduction. You can also buy host-level software to do this. And of course, you can buy storage products that do this too. So which is best? It probably depends on which vendor you ask (i.e. database, host-level or storage), since each one is chasing revenue for that option – and in some storage vendor cases the data reduction is “always on”, which means you get it whether you want it or not (and whether you want to pay for it or not). But what you should know is this: your friendly flash storage vendor has the most to gain or lose when it comes to data reduction software.

Lies, Damned Lies and Capacities

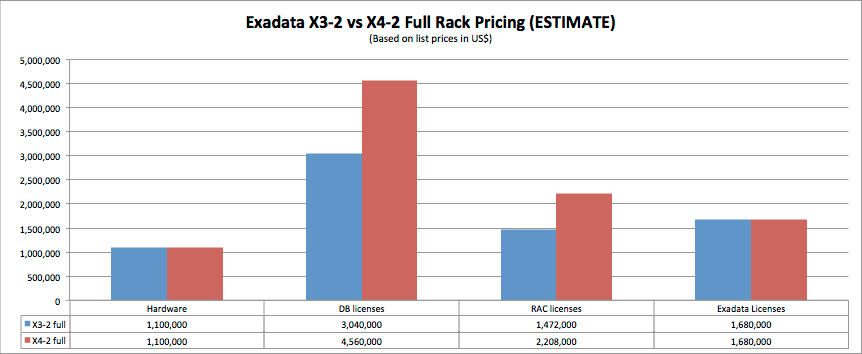

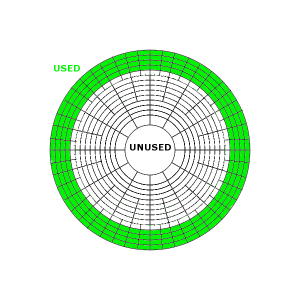

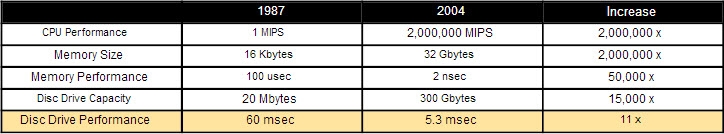

When you purchase storage, you invariably buy it at a value based on price per usable capacity, most commonly using the unit of dollars per GB. This is simply a convenient way of comparing the price of competing products which may otherwise have different capacities: if a storage array costs $X and gives you Y GB of usable capacity, then the price in $/GB (dollars per gig) is therefore X/Y.

Now this practice originally developed when buying disk arrays – and there are some arguments to be made that $/GB carries less significance with flash… but everyone does it. Even if you aren’t doing it, chances are somebody in your purchasing department is. And even though it may not be the best way to compare two different products, you can bet that the vendor whose product has the lowest $/GB price will be the one looking most comfortable when it comes to decision day.

But what if there was a way to massage those figures? Each vendor wants to beat the competition, so they start to say things like, “Hey, what about if you use our storage compression features? On average our customers see a 10x reduction in data. This means the usable capacity is actually 10Y!“. Wouldn’t you know it? The price per gig (which is now X/10Y) just came down by 90%!

The First Rule of Compression

You all know this, but I’m going to say it anyway. Different sets of data result in different levels of compression (and deduplication). It’s obvious. Yet in the sterile environment of datasheets and TCO calculations it often gets overlooked. So let me spell it out for once and for all:

The first rule of compression is that the compression ratio is entirely dependant on the data being compressed.

Thus if you are buying or selling a product that uses compression, deduplication and data reduction, you cannot make any guarantees. Sure you can talk about “average compression ratios”, but what does that mean? Is there really such a thing as the average dataset?

Conclusion: Know What You Are Paying For

It’s a very simple message: when you buy a flash array (or indeed any storage array) be sure to understand the capacity values you are buying and paying for. Dollar per GB values are only relevant with usable capacities, not so-called effective or logical capacities. Also, don’t get too hung up on raw capacity values, since they won’t help you when you run out of usable space.

Definitions are important. Without them, nothing we talk about is … well, definite. So here are mine: