As anyone familiar with the use of Oracle on Advanced Format storage devices will know to their cost, Oracle has had some difficulties implementing support of 4k devices. Officially, support for devices with a 4096 byte sector size was introduced in Oracle 11g Release 2 (see section 4.8.1.4 of the New Features Guide) but actually, if the truth be told, there were some holes.

(Before reading on, if you aren’t sure what I’m talking about here then please have a read of this page…)

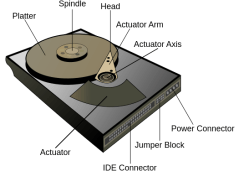

I should say at this point that most 4k Advanced Format storage products have the ability to offer 512 byte emulation, which means any of the problems shown here can be avoided with very little effort (or performance overhead), but since 4096 byte devices are widely expected to take over, it would be nice if Oracle could tighten up some of the problems. After all, it’s not just flash memory devices that tend to be 4k-based: Toshiba, HGST, Seagate and Western Digital are all making hard disk drives that use Advanced Format too.

The SPFILE Problem in <11.2.0.4

Given that 4k devices are allegedly supported in Oracle 11g Release 2 you would think it would make sense that you can provision a load of 4k LUNs and then install the Oracle Grid Infrastructure and Database software on them. But no, in versions up to and including 11.2.0.3 this caused a problem with the SPFILE.

Here’s my sample system. I have 10 LUNs all with a physical and logical blocksize of 4k. I’m using Oracle’s ASMLib kernel driver to present them to ASM and the 4k logical and physical properties are preserved through into the ASMLib device too:

[root@half-server4 mapper]# fdisk -l /dev/mapper/slobdata1 | grep "Sector size"

Sector size (logical/physical): 4096 bytes / 4096 bytes

[root@half-server4 mapper]# oracleasm querydisk /dev/mapper/slobdata1

Device "/dev/mapper/slobdata1" is marked an ASM disk with the label "SLOBDATA1"

[root@half-server4 mapper]# fdisk -l /dev/oracleasm/disks/SLOBDATA1 | grep "Sector size"

Sector size (logical/physical): 4096 bytes / 4096 bytes

Next I’ve installed 11.2.0.3 Grid Infrastructure and created an ASM diskgroup on these LUNs. As you can see, Oracle has successfully spotted the devices are 4k and correspondingly set the ASM diskgroup sector size to 4096:

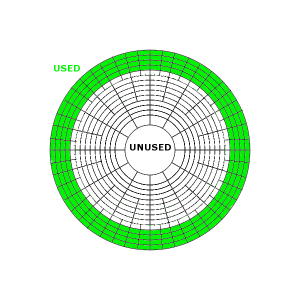

ASMCMD> lsdg

State Type Rebal Sector Block AU Total_MB Free_MB Req_mir_free_MB Usable_file_MB Offline_disks Voting_files Name

MOUNTED EXTERN N 4096 4096 1048576 737280 737207 0 737207 0 N DATA/

Time to install the database. I’ll just fire up the 11.2.0.3 OUI and install the database software complete with a default database, choosing to locate the database files in this +DATA diskgroup. What could possibly go wrong?

The installer gets as far as running the database configuration assistant and then crashes out with the message:

PRCR-1079 : Failed to start resource ora.orcl.db

CRS-5017: The resource action "ora.orcl.db start" encountered the following error:

ORA-01078: failure in processing system parameters

ORA-15081: failed to submit an I/O operation to a disk

ORA-27091: unable to queue I/O

ORA-17507: I/O request size 512 is not a multiple of logical block size

ORA-06512: at line 4

. For details refer to "(:CLSN00107:)" in "/home/OracleHome/product/11.2.0/grid/log/half-server4/agent/ohasd/oraagent_oracle/oraagent_oracle.log".

Why did this happen? The clue is in the error message highlighted in red. Over the years that this has been happening (and trust me, it’s been happening for far too long) various notes have appeared on My Oracle Support, such as 1578983.1 and 14626924.8. The cause is the following bug:

Bug 14626924 Not able to read spfile from ASM diskgroup and disk with sector size of 4096

At the time of writing, this bug is shown as fixed in 11.2.0.4 and the 12.2 forward code stream, with backports available for 11.2.0.2.0, 11.2.0.3.0, 11.2.0.3.7, 12.1.0.1.0 and 12.1.0.1.2. Alternatively, there is the simple workaround (documented in my Install Cookbooks) of placing the SPFILE in a non-4k location.

What the heck, I have the 11.2.0.4 binaries stored locally, so let’s fire it up and see the fixed SPFILE in action.

11.2.0.4 with 4k Devices

As with the previous example, I have a set of 4k LUNs presented via ASMLib – I won’t repeat the output from above as it’s identical. The ASM diskgroup correctly shows the sector size as 4096, so we’re ready to install the database software and let it create a database. As before the database files will be located in the diskgroup – including the SPFILE – but this time, it won’t fail because bug 14626924 is fixed in 11.2.0.4 right? Right?

Oh dear. That’s not the error-free installation we were hoping for. Also, one of my pet hates, why are these Clusterware messages so incredibly unhelpful? Looking in the oraagent_oracle.log file we find the following nugget of information:

ORA-01034: ORACLE not available

ORA-27101: shared memory realm does not exist

Linux-x86_64 Error: 2: No such file or directory

Process ID: 0

Session ID: 0 Serial number: 0

That’s not entirely useful either, so let’s try and fire up the database manually:

[oracle@half-server4 ~]$ sqlplus / as sysdba

SQL*Plus: Release 11.2.0.4.0 Production on Wed Feb 12 17:56:29 2014

Copyright (c) 1982, 2013, Oracle. All rights reserved.

Connected to an idle instance.

SQL> startup nomount

ORA-01078: failure in processing system parameters

ORA-17510: Attempt to do i/o beyond file size

Aha! The problem happens even attempting to start in NOMOUNT mode, so it seems likely this is related to reading the PFILE or SPFILE. Let’s just check to see what we have:

[oracle@half-server4 ~]$ ls -l $ORACLE_HOME/dbs/initorcl.ora

-rw-r----- 1 oracle oinstall 35 Feb 12 17:26 /u01/app/oracle/product/11.2.0/dbhome_1/dbs/initorcl.ora

[oracle@half-server4 ~]$ cat $ORACLE_HOME/dbs/initorcl.ora

SPFILE='+DATA/orcl/spfileorcl.ora'

Sure enough, we have an SPFILE located in the ASM diskgroup… and we cannot read it. Could it possibly be that even in 11.2.0.4 there are problems with SPFILEs being located in 4k devices? Searching My Oracle Support for ORA-17510 initially draws a blank. But a search of the Oracle bug database for the previous bug number (14626924) brings up some interesting new bugs:

Bug 16870214 : DB STARTUP FAILS WITH ORA-17510 IF SPFILE IS IN 4K SECTOR SIZE DISKGROUP

In the description of this bug, the following statement is made:

PROBLEM:

--------

ORA-17510: Attempt to do i/o beyond file size after applying patch 14626924

TO READ SPFILE FROM ASM DISKGROUP AND DISK WITH SECTOR SIZE OF 4096

DIAGNOSTIC ANALYSIS:

--------------------

1. create init file initvarial.ora in dbs directory with below

spfile='+DATA1/VARIAL/spfilevarial.ora'

2. startup pfile=/u01/app/oracle/product/11.2.0.3/db_1/dbs/initvarial.ora

SQL> startup pfile=/u01/app/oracle/product/11.2.0.3/db_1/dbs/initvarial.ora

ORA-17510: Attempt to do i/o beyond file size

This looks very similar. Unfortunately this bug is marked as a duplicate of base bug 18016679, which sadly is unpublished. All we know about it is that, at the time of writing, it isn’t fixed – the status of the duplicate is still “Waiting for the base bug fix“.

So there we have it. The infamous 4k SPFILE issue is fixed in 11.2.0.4 and replaced with something else that makes it equally unusable. For now, we’ll just have to keep those SPFILEs in 512 byte devices…

Update Feb 14th 2014

I kind of had a feeling that the above problem was in some way related to the use of ASMLib, so I thought I’d repeat the entire 11.2.0.4 install using normal block devices. Essentially this means changing the ASM discovery path from it’s default value of ‘ORCL:*’ to the path of the device mapper multipath devices, which is my case is ‘/dev/mapper/slob*’.

This time we don’t even get through the Grid Infrastructure installation, which fails while running the Oracle ASM Configuration Assistance (asmca) giving the following error messages:

[main] [ 2014-02-14 15:55:22.112 GMT ] [UsmcaLogger.logInfo:143] CREATE DISKGROUP SQL: CREATE DISKGROUP DATA EXTERNAL REDUNDANCY DISK '/dev/mapper/slobdata1', '/dev/mapper/slobdata2', '/dev/mapper/slobdata3', '/dev/mapper/slobdata4',

'/dev/mapper/slobdata5', '/dev/mapper/slobdata6', '/dev/mapper/slobdata7', '/dev/mapper/slobdata8'

ATTRIBUTE 'compatible.asm'='11.2.0.0.0','au_size'='1M'

[main] [ 2014-02-14 15:55:22.206 GMT ] [SQLEngine.done:2189] Done called

[main] [ 2014-02-14 15:55:22.224 GMT ] [UsmcaLogger.logException:173] SEVERE:method oracle.sysman.assistants.usmca.backend.USMDiskGroupManager:createDiskGroups

[main] [ 2014-02-14 15:55:22.224 GMT ] [UsmcaLogger.logException:174] ORA-15018: diskgroup cannot be created

ORA-27061: waiting for async I/Os failed

It seems Oracle still has some way to go before this will work properly…