Everyone is talking about In Memory at the moment. On blogs, in tweets, in the press, in the Oracle marketing department, in books by SAP employees, even my Violin colleagues… it’s everywhere. What can I possibly add that will be of any value?

Everyone is talking about In Memory at the moment. On blogs, in tweets, in the press, in the Oracle marketing department, in books by SAP employees, even my Violin colleagues… it’s everywhere. What can I possibly add that will be of any value?

Well, how about owning up to something: I find myself in a bit of a quandary on this subject. On the one hand it’s a new buzzword, which means that a) it’s got everyone’s attention, and b) many people with their own agenda will seek to use it to their advantage… but on the other hand, given the nature of my employment (I work for Violin Memory, purveyors of flash memory systems), it seems like something we ought to be talking about.

As anyone who works in the IT industry knows (and perhaps it’s the same in other industries), we love a buzzword. Cloud, Analytics, Big Data, In Memory, Transformation… all of these phrases have been used at one time or another to try and wring cash out of customers who may or may not need the services and products they imagine the phrase represents. Even back at the end of the last millenium consultants worldwide were making huge amounts of money out of exploiting the phrase “Y2K”, some with more honourable intentions than others. I remember my old school received a letter from a “Y2K conformance specialist” informing them that this person could visit and inspect their football pitches to ensure they were “Y2K compliant”… (true story!)

So if buzzwords are prone to misuse, maybe the first thing we need to do is explore what “In Memory” really means? In fact, rewind a step – what do we mean when we say “Memory”?

What Is Memory?

It’s a basic question, but a good definition is surprisingly hard to pin down. Clearly this is an IT blog so (despite the deceiving picture above) I am only interested in talking about computer memory rather than the stuff in my head which stops working after I drink tequila. The definition of this term in the Free Online Dictionary of Computing is:

memory: These days, usually used synonymously with Random Access Memory or Read-Only Memory, but in the general sense it can be any device that can hold data in machine-readable format.

So that’s any device that can hold data in machine-readable format. So far so ambiguous. And of course that is the perfect situation for any would-be freeloader to exploit, since the less well-defined a definition is, the more room there is to manoeuvre any product into position as a candidate for that description.

Here’s what most people think of when they talk about computer memory… DRAM:

This is Dynamic Random Access Memory – and it’s most likely what’s in your laptop, your desktop and your servers. You know all about this stuff – it’s fast, it’s volatile (i.e. the data stored on it is lost when the power goes off) and it’s comparatively expensive to say… disk, for which many orders of magnitude more are available at the same price point.

But now there is a new type of “memory” on the market, NAND flash memory. Actually it’s been around for over 25 years (read this great article for more details) but it is only now that we are seeing it being adopted en mass in data-centres, as well as being prevalent in consumer devices – the chances are your phone contains NAND flash, your tablet (if you have one) and maybe your computer if you are fortunate enough to have an SSD drive in it.

Flash memory, unlike DRAM, is persistent. That means when the power goes, the data remains. Flash access speeds are measured in microseconds – let’s say around 100 microseconds for a single random access. That’s significantly faster than disk, which is measured in (multiple) milliseconds – but still slower than DRAM, for which you would expect an access in around 100 nanoseconds. Flash is available in many forms, from USB devices and SSDs which fit into normal hard drive bays, through PCIe cards which connect direct to the system bus, and on to enterprise-class storage arrays such as those made by my employer like the Violin Memory 6000 series array.

Is flash a type of memory? It certainly fits the dictionary description above. But if you run something on flash, can you describe that something as now running “in memory”? You could argue the point either way I suppose.

Since we don’t seem to be doing well with defining what memory is, let’s change tack and talk about what it definitely isn’t. And that’s simple, because it definitely isn’t disk.

Whether it’s part of the formal definition or not, almost anyone would assume that memory is fast and non-mechanical, i.e. it has no moving parts. It is all semiconductors and silicon, not motors and magnets. A hard disk drive, with its rotating platters and moving actuator arm, is about the most un-memory-like way you can find to store your data, short of putting it on a big reel of tape. And, consistent with our experience of memory versus non-memory devices, it’s slow. In fact, every disk array vendor in the industry stuffs their enterprise disk arrays full of DRAM caches to make up for the slow performance of disk. So memory is something they use to mask the speed of their non-memory-based storage. Hang on then, if you have a small enough dataset so that the majority of your disk reads are coming from your disk array cache, does that mean you are running “in memory” too? No of course not, but the ambiguity is there to be exploited.

Primary Storage versus Secondary Storage

Since we are struggling with a formal definition of memory, perhaps another way to look at it is in terms of primary storage and secondary storage. The main difference here is that primary storage is directly addressable by the CPU, whereas secondary storage is addressed through input/output channels. Is that a good way of distinguishing memory from non-memory? It certainly works with DRAM, which ends up in the primary storage category, as well as disk, which ends up in the secondary storage category. But with flash it is a less successful differentiator.

The first problem is that as previously mentioned flash is available in multiple different forms. PCIe flash cards are directly addressable by the CPU whilst SSDs slot into hard drive bays and are accessed using storage protocols. In fact, just looking at the Violin Memory 6000 series array around which my day job revolves, connectivity options include PCIe direct attached, fibre-channel and Infiniband, meaning it could easily fit into either of the above categories.

What’s more, if you think of primary storage as somehow being faster than secondary storage, the Infiniband connectivity option of the Violin array is only about 50-100 microseconds slower than the PCIe version, yet brings a wealth of additional benefits such as high availability. It’s hard to think of a reason why you would choose the direct attached version of that with Infiniband.

Volatile versus Persistent

Maybe this is a better method of differentiating? Perhaps we can say that memory is that which is volatile, i.e. data stored on it will be lost when power is no longer available. The alternative is persistent storage, where data exists regardless of the power state. Does that make sense?

Not really. Think about your traditional computer, whether it’s a desktop or server. You have four high-level resources: CPU to do the work, network to communicate with the outside world, disk to store your data (the persistence layer). Why do you have memory in the form of DRAM? Why commit extra effort to managing a volatile store of data, much of which is probably duplicated on the persistence layer?

Not really. Think about your traditional computer, whether it’s a desktop or server. You have four high-level resources: CPU to do the work, network to communicate with the outside world, disk to store your data (the persistence layer). Why do you have memory in the form of DRAM? Why commit extra effort to managing a volatile store of data, much of which is probably duplicated on the persistence layer?

DRAM exists to drive up CPU utilisation. Processor speeds have famously doubled every couple of years or so. Network speeds have also increased drastically since the days of the 56k modem I used to struggle with in the 1990’s. Disk hasn’t – nowhere near in fact. Sure, capacity has increased – and speeds have slowly struggled upwards until they reached the limit of the 15k RPM drive, but in comparison to CPU improvements disk has been absolutely stagnant. So your computer is stuffed full of DRAM because, if it weren’t, the processors would spend all their time waiting for I/O instead of doing any work. By keeping as much data in volatile DRAM as possible, the speed of access is increased by around five orders of magnitude, resulting in CPUs which can spend more time working and less time waiting.

In the world of flash memory things are slightly different. DRAM is still necessary to maintain CPU utilisation, because flash is around two-and-a-half to three orders of magnitude slower than DRAM. But does it make sense to assume that “memory” is therefore only applicable to volatile data storage? What if a hypothetical persistent flash medium arrived with DRAM access speeds? Would we refuse to say that something running on this magic new media was running “In Memory”?

In the world of flash memory things are slightly different. DRAM is still necessary to maintain CPU utilisation, because flash is around two-and-a-half to three orders of magnitude slower than DRAM. But does it make sense to assume that “memory” is therefore only applicable to volatile data storage? What if a hypothetical persistent flash medium arrived with DRAM access speeds? Would we refuse to say that something running on this magic new media was running “In Memory”?

I don’t have an answer, only an opinion. My opinion is that memory is solid-state semiconductor-based storage and can be volatile or persistent. DRAM is a type of memory, but not the only type. Flash is a type of memory, while disk clearly is not.

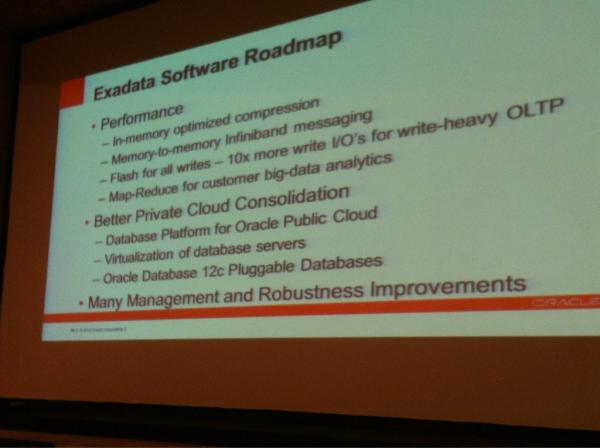

So with that in mind, in the next part of this blog series I’m going to look at In Memory Database technologies and describe what I see as the three different architectures of IMDB that are currently available. As a taster, one of them is SAP HANA, one of them involves Violin Memory and the third one is the new Oracle Exadata X3 “Database In-Memory Machine”. And as a conclusion I will have to make a decision about the quandary I mentioned at the start of this article: should we at Violin claim a piece of the “In Memory” pie?

In

In

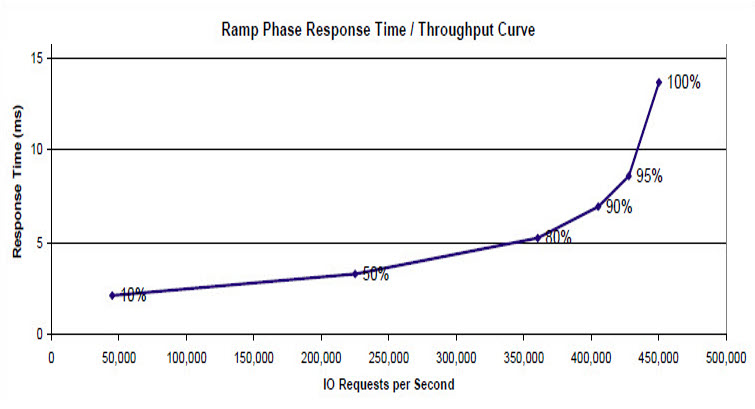

One thing you do not want to happen when you virtualise your databases onto a consolidated physical platform is to find the ceiling of your I/O capabilities. Every storage system has an upper limit of the number of I/O operations that it can perform per second (known as IOPS) and when that ceiling is reached (known as saturation) things can get painful.

One thing you do not want to happen when you virtualise your databases onto a consolidated physical platform is to find the ceiling of your I/O capabilities. Every storage system has an upper limit of the number of I/O operations that it can perform per second (known as IOPS) and when that ceiling is reached (known as saturation) things can get painful.