Storage for DBAs: The strange thing about enterprise databases is that the people who design, manage and support them are often disassociated from the people who pay the bills. In fact, that’s not unusual in enterprise IT, particularly in larger organisations where purchasing departments are often at opposite ends of the org chart to operations and engineering staff.

Storage for DBAs: The strange thing about enterprise databases is that the people who design, manage and support them are often disassociated from the people who pay the bills. In fact, that’s not unusual in enterprise IT, particularly in larger organisations where purchasing departments are often at opposite ends of the org chart to operations and engineering staff.

I know this doesn’t apply to everyone but I spent many years working in development, operations and consultancy roles without ever having to think about the cost of an Oracle license. It just wasn’t part of my remit. I knew software was expensive, so I occasionally felt guilt when I absolutely insisted that we needed the Enterprise Edition licenses instead of Standard Edition (did we really, or was I just thinking of my CV?) but ultimately my job was to justify the purchase rather than explain the cost.

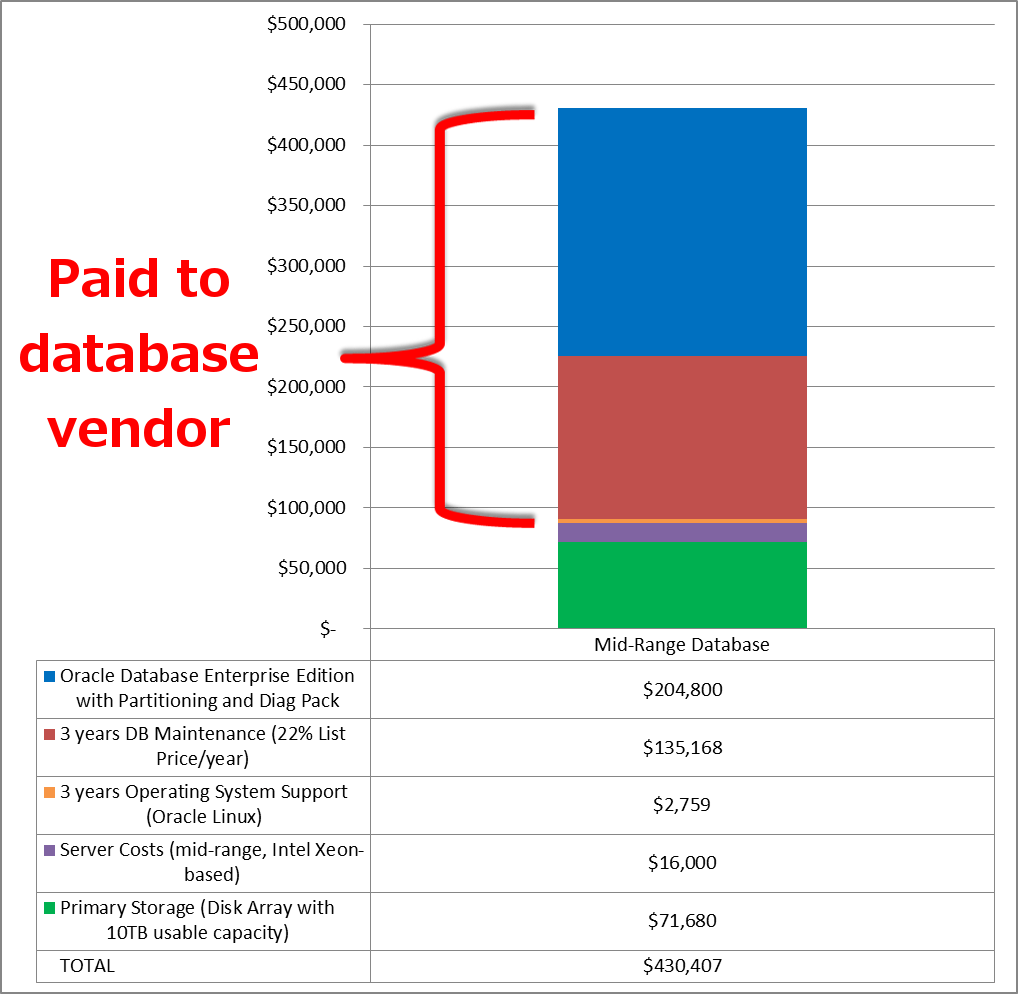

On the off chance that there are people like me out there who are still a little bit in the dark about pricing, I’m going to use this post to describe the basic price breakdown of a database environment. I also have a semi-hidden agenda for this, which is to demonstrate the surprisingly small proportion of the total cost that comprises the storage system. If you happen to be designing a database environment and you (or your management) think the cost of high-end storage is prohibitive, just keep in mind how little it affects the overall three-year cost in comparison to the benefits it brings.

Pricing a Mid-Range Oracle Database

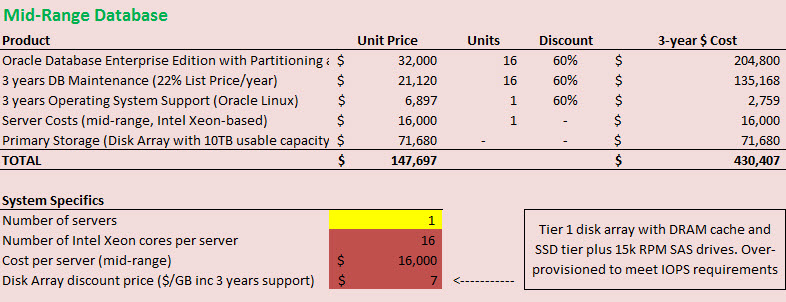

Let’s take a simple mid-range database environment as our starting point. None of your expensive Oracle RAC licenses, just Enterprise Edition and one or two options running on a two-socket server.

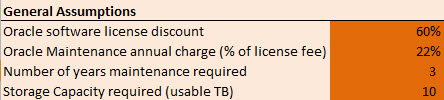

At the moment, on the Oracle Store, a perpetual license for Enterprise Edition is retailing at $47,500 per processor. We’ll deal with the whole per processor thing in a minute. Keep in mind that this is the list price as well. Discounts are never guaranteed, but since this is a purely hypothetical system I’m going to apply a hypothetical 60% discount to the end product later on.

I said one or two options, so I’m going to pick the Partitioning option for this example – but you could easily choose Advanced Compression, Active Data Guard, Spatial or Real Application Testing as they are all currently priced at $11,500 per processor (with the license term being perpetual – if you don’t know the difference between this and named user then I recommend reading this). For the second option I’ll pick one of the cheaper packs… none of us can function without the wait interface anymore, so let’s buy the Tuning Pack for $5,000 per processor.

The Processor Core Factor

I guess we’d better discuss this whole processor thing now. Oracle uses per core licensing which means each CPU core needs a license, as opposed to per socket which requires one license per physical chip in the server. This is normal practice these days since not all sockets are equal – different chips can have anything from one to ten or more cores in them, making socket-based licensing a challenge for software vendors. Sybase is licensed by the core, as is Microsoft SQL Server from SQL 2012. However, not all cores are equal either… meaning that different types of architecture have to be priced according to their ability.

The solution, in Oracle’s case, is the Oracle Processor Core Factor, which determines a multiplier to be applied to each processor type in order to calculate the number of licenses required. (At the time of writing the latest table is here but always check for an updated version.) So if you have a server with two sockets containing Intel Xeon E5-2690 processors (each of which has eight cores, giving a total of sixteen) you would multiply this by Oracle’s core factor of 0.5 meaning you need a total of 16 x 0.5 = 8 licenses. That’s eight licenses for Enterprise Edition, eight licenses for Partitioning and eight licenses for the Tuning Pack.

What else do we need? Well there’s the server cost, obviously. A mid-range Xeon-based system isn’t going to be much more than $16,000. Let’s also add the Oracle Linux operating system (one throat to choke!) for which Premier Support is currently listing at $6,897 for three years per system. We’ll need Oracle’s support and maintenance of all these products too – traditionally Oracle sells support at 22% of the net license cost (i.e. what you paid rather than the list price), per year. As with everything in this post, the price / percentage isn’t guaranteed (speak to Oracle if you want a quote) but it’s good enough for this rough sketch.

Finally, we need some storage. Since I’m actually describing from memory an existing environment I’ve worked on in the past, I’m going to use a legacy mid-range disk array priced at $7 per GB – and I want 10TB of usable storage. It’s got some SSD in it and some DRAM cache but obviously it’s still leagues apart from an enterprise flash array.

Price Breakdown

That’s everything. I’m not going to bother with a proper TCO analysis, so these are just the costs of hardware, software and support. If you’ve read this far your peripheral vision will already have taken in the graph below. so I can’t ask you to take a guess… but think about your preconceptions. Of the total price, how much did you think the storage was going to be? And how much of the total did you think would go to the database vendor?

The storage is just 17% of the total, while the database vendor gets a whopping 80%. That’s four-fifths… and they don’t even have to deal with the logistics of shipping and installing a hardware product!

Still, the total price is “only” $430k, so it’s not in the millions of dollars, plus you might be able to negotiate a better discount. But ask yourself this: what would happen if you added Oracle Real Application Clusters (currently listing at $23,000 per processor) to the mix. You’d need to add a whole set of additional nodes too. The price just went through the roof. What about if you used a big 80-core NUMA server… thereby increasing the license cost by a factor of five (16 cores to 80)? Kerching!

Performance and Cost are Interdependent

There are two points I want to make here. One is that the cost of storage is often relatively small in terms of the total cost. If a large amount of money is being spent on licensing the environment it makes sense to ensure that the storage enables better performance, i.e. results in a better return on investment.

There are two points I want to make here. One is that the cost of storage is often relatively small in terms of the total cost. If a large amount of money is being spent on licensing the environment it makes sense to ensure that the storage enables better performance, i.e. results in a better return on investment.

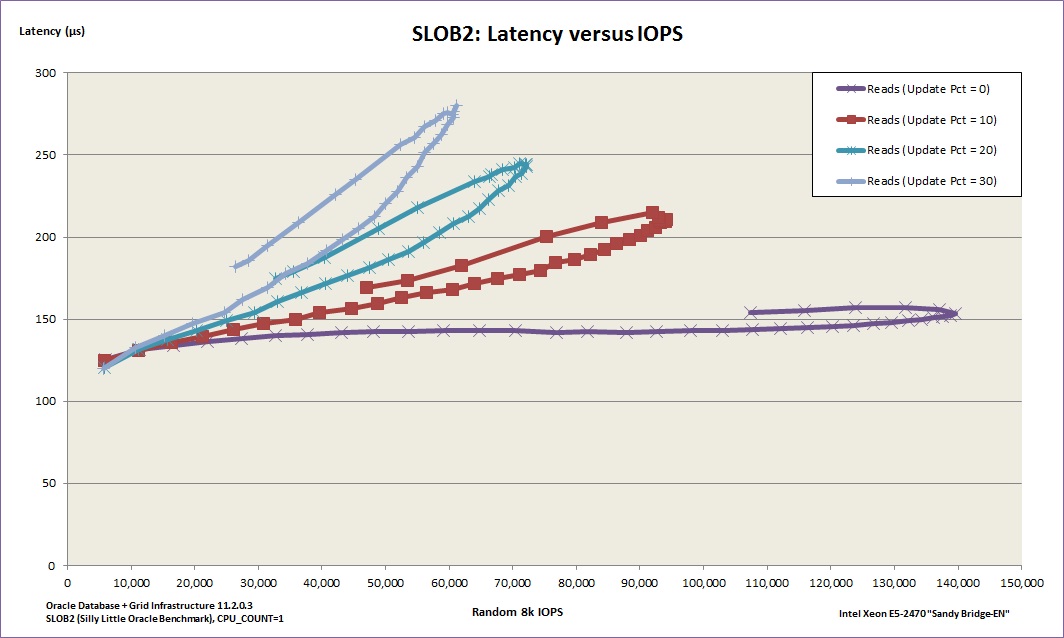

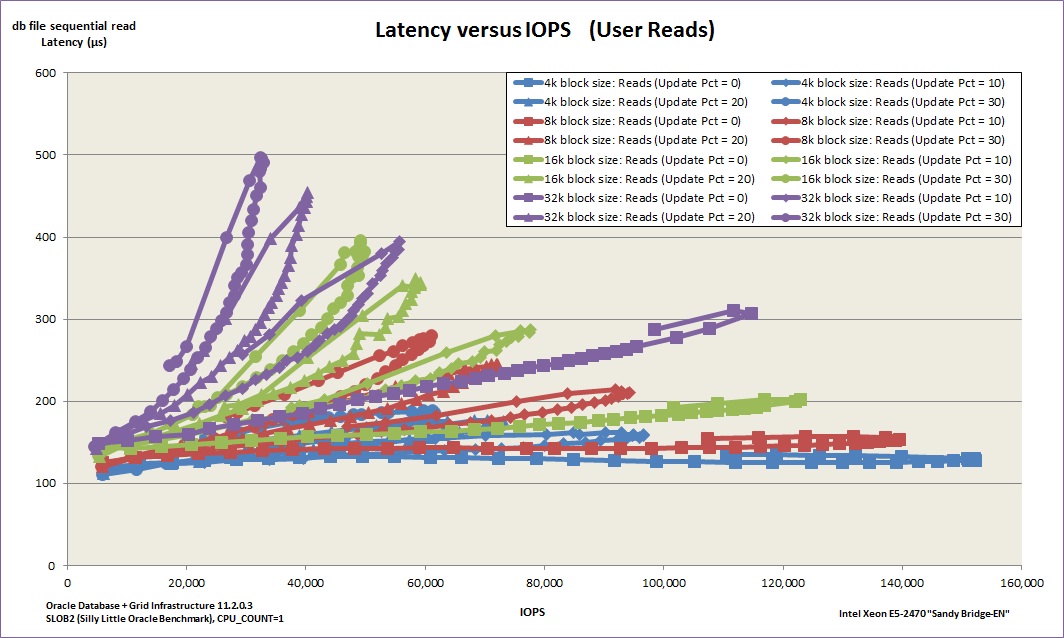

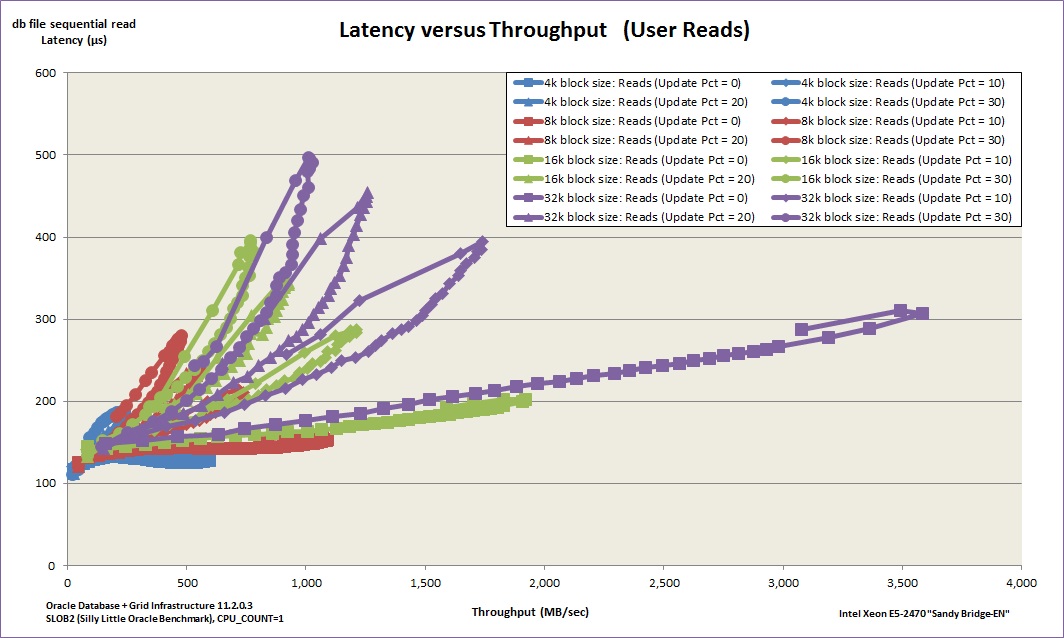

The second point is more subtle – but even more important. Look at the price calculations above and think about how important the number of CPU cores is. It makes a massive difference to the overall cost, right? So if that’s the case, how important do you think it is that you use the best CPUs? If CPU type A gives significantly better performance than CPU type B, it’s imperative that you use the former because the (license-related) cost of adding more CPU is prohibitive.

Yet many environments are held back by CPUs that are stuck waiting on I/O. This is bad news for end users and applications, bad news for batch jobs and backups. But most of all, this is terrible news for data centre economics, because those CPUs are much, much more expensive than the price you pay to put them in the server.

There is more to come on this subject…

Forget everything else. Latency is the critical factor because this is what injects delay into your system. Latency means lost time; time that could have been spent busily producing results, but is instead spent waiting for I/O resources.

Forget everything else. Latency is the critical factor because this is what injects delay into your system. Latency means lost time; time that could have been spent busily producing results, but is instead spent waiting for I/O resources.

Short post to point out that I’ve now posted the updated

Short post to point out that I’ve now posted the updated