As part of the Installation Cookbook series I have now posted a new entry on how to install Oracle VM with Violin Memory flash storage:

As part of the Installation Cookbook series I have now posted a new entry on how to install Oracle VM with Violin Memory flash storage:

Tag: database

Database Workload Theory

In the scientific world, theoretical physicists postulate theories and ideas, for example the Higgs Boson. After this, experimental physicists design and implement experiments, such as the Large Hadron Collider, to prove or disprove these theories. In this post I’m going to try and do the same thing with databases, except on a smaller budget, with less glamour and zero chance of winning a Nobel prize. On the plus side though, my power bills will be a lot lower.

That last paragraph was really just a grandiose way of saying that I have an idea, but haven’t yet thought of a way to prove it. I’m open to suggestions, feedback and data which prove or disprove it… but for now let’s just look at the theory.

Visualising Database Server I/O Workload

If you look at a database server running a real life workload, you will generally see a pattern in the behaviour of the I/O. If you plot a graph of the two extremes of purely sequential I/O and purely random I/O most workloads will fit somewhere along this sliding scale :

Now of course workloads change all the time, so this is an approximation or average, but it makes sense. After all, we do this in the world of storage, because if the workload is highly random the storage requirements will be very different to if the workload is highly sequential.

What I am going to do now is plot a graph with this as the horizontal axis. The vertical axis will be an exponential representation of the storage footprint used by the database server, i.e. the amount of space used. I can then plot different database server workloads on the graph to see where they fall.

But first, two clarifications. I am at pains to say “database server” instead of “database” because in many environments there are multiple database instances generating I/O on the same server. What we are interested in here is how the storage system is being driven, not how each individual database is behaving. Remember this point and I’ll come back to it soon. The other clarification is regarding workload – because many systems have different windows where I/O patterns change. The classic (and very common) example is the OLTP database where users log off at the end of the day and then batch jobs are run. Let’s plot the OLTP and batch workloads as separate points on our graph.

Here’s what I expect to see:

There are data points in various places but a correlation is visible which I’ve highlighted with the blue line. Unfortunately this line is nothing new or exciting, it’s just a graphical representation of the fact that large databases tend to perform lots of sequential I/O whereas small databases tend to perform lots of random I/O.

Why is that? Well because in most cases large databases tend to be data warehouses, decision support systems, business intelligence or analytics systems… places where data is bulk loaded through ETL jobs and then scanned to create summary information or spot trends and patterns. Full table scans are the order of the day, hence sequential I/O. On the other hand, smaller databases with lots of random I/O tend to be OLTP-based, highly transactional systems running CRM, ERM or e-Commerce platforms, for example.

Still, it’s a start – and we can visualise this by dividing the graph up into quadrants and calling them zones, like this:

This is only an approximation, but it does help with visualising the type of I/O workload generated by database servers. However, there are two more quadrants looking conspicuously un-labelled, so let’s now turn our attention to them.

This is only an approximation, but it does help with visualising the type of I/O workload generated by database servers. However, there are two more quadrants looking conspicuously un-labelled, so let’s now turn our attention to them.

Database Consolidation I/O Workload

The bottom left quadrant is not very exciting, because small database systems which generate highly-sequential workloads are rare. I have worked on one or two, but none that I ever felt should actually have been designed to work that way. (One was an indexing system which got scrapped and replaced with Lucene, the other I am still not sure actually existed or if it was just a bad dream that I once had…)

The top right quadrant is much more interesting, because this is the world of database consolidation. I said I would come back to the idea that we are interested not in the workload of the database but of the database server. The reason for this is that as more databases are run on the same server and storage infrastructure, the I/O will usually become increasingly random. If you think about multiple sets of disparate users working on completely different applications and databases, you realise that it quickly becomes impossible to predict any pattern in the behaviour of the I/O. We already know this from the world of VDI, where increasing the number of seats results in an increasingly random I/O requirement.

The top right quadrant requires lots of random I/O and yet is large in capacity. Let’s label it the consolidation zone on our graph:

We now have a graphical representation of three broad areas of I/O workload. If we believe in the trend of database consolidation, as described by the likes of Gartner and IDC, then over time the dots in the DW and OLTP zones will migrate to the consolidation zone. I have already blogged my thoughts on the benefits of database consolidation, bringing with it increased agility and massive savings in operational costs (especially Oracle licenses) – and many of the customers I have been speaking to both at Violin and in my previous role are already on this journey, even if some are still in the planning stages. I therefore expect to see this quadrant become increasingly populated with workloads, particularly as flash storage technologies take away the barriers to entry.

I/O Workload Zone Requirements

The final step in this process is to look at the generic requirements of each of our three workload zones.

The data warehouse zone is relatively straightforward, because what these systems need more than anything is bandwidth. Also known as throughput, this is the ability of the storage to pump large volumes of data in and out. There is competition here, because whilst flash memory systems can offer excellent throughput, so can disk systems. So can Exadata of course, it’s what it was designed for. Mind you, flash should enable a lower operational cost, but this isn’t a sales pitch so let’s move on to the next zone.

The OLTP zone is all about latency. To run a highly-transactional system and get good performance and end-user experience, you need consistently low latency. This is where flash memory excels – and disk sucks. We all (hopefully) know why – disk simply cannot overcome the seek time and rotational latency inherent in its design.

The consolidation zone however is particularly interesting, because it has a subtly different set of requirements. For consolidation you need two things: the ability to offer sustained high levels of IOPS, plus predictable latency. Obviously when I say that I mean predictably low, because predictably high latency isn’t going to cut it (after all, that’s what disk systems deliver). If you are running multiple, disparate applications and databases on the same infrastructure (as is the case with consolidation) it is crucial that each does not affect the performance of the other. One system cannot be allowed to impact the others if it misbehaves.

Now obviously disk isn’t in with a hope here – highly random I/O driving massive and sustained levels of IOPS is the worst nightmare for a disk system. For flash it’s a different story – but it’s not plain sailing. Not every flash vendor can truly sustain their performance levels or keep their latency spike-free. Additionally, not every flash vendor has the full set of enterprise features which allow their products to become a complete tier of storage in a consolidation environment.

As database consolidation increases – and in fact accelerates with the continued onset of virtualisation – these are going to be the requirements which truly differentiate the winners from the contenders in the flash market.

It’s going to be fun…

Disclaimer

These are my thoughts and ideas – I’m not claiming them as facts. The data here is not real – it is my attempt at visualising my opinions based on experience and interaction with customers. I’m quite happy to argue my points and concede them in the face of contrary evidence. Of course I’d prefer to substantiate them with proof, but until I (or someone else) can devise a way of doing that, this is all I have. Feel free to add your voice one way or the other… and yes, I am aware that I suck at graphics.

These are my thoughts and ideas – I’m not claiming them as facts. The data here is not real – it is my attempt at visualising my opinions based on experience and interaction with customers. I’m quite happy to argue my points and concede them in the face of contrary evidence. Of course I’d prefer to substantiate them with proof, but until I (or someone else) can devise a way of doing that, this is all I have. Feel free to add your voice one way or the other… and yes, I am aware that I suck at graphics.

Auto DOP with High Performance Storage

Guest Post

Nate Fuzi is my friend and collegue, based out in the US fulfilling the same role that I perform in EMEA. He is also the person with which I have drunk more sake jello shots than I ever thought probable / sensible / acceptable. Nate recently wrote this note regarding the use of Oracle’s Automatic Degree of Parallelism with Violin Memory flash storage – and I liked it so much I asked him if I could re-blog it for the Internet community. I suspect I will have to offer him some sort of sake jello shot-based payment, but I am prepared to suffer this so that you, the reader, do not have to. My pain is your gain. Over to you Nate…

Who among us is not a fan of Auto DOP (Automatic Degree of Parallelism) in Oracle 11gR2? This easy button was supposed to take all the stress out of handling parallelism inside the database: no more setting non-default degrees on tables, no need to put parallel hints in SQL, etc. According to so many blogs, all you had to do was set PARALLEL_DEGREE_POLICY to AUTO, and the parallelism fairy sprinkled her dust in just the right places to make your multi-threaded dreams come true.

Who among us is not a fan of Auto DOP (Automatic Degree of Parallelism) in Oracle 11gR2? This easy button was supposed to take all the stress out of handling parallelism inside the database: no more setting non-default degrees on tables, no need to put parallel hints in SQL, etc. According to so many blogs, all you had to do was set PARALLEL_DEGREE_POLICY to AUTO, and the parallelism fairy sprinkled her dust in just the right places to make your multi-threaded dreams come true.

[If you don’t care to read ALL about my pain and suffering, skip down to #MEAT]

But she vexed me time and again—in multiple POCs where high core count systems failed to launch more than a couple oracle processes at a time and where I finally resorted back to the old ways to achieve what I knew the Violin array was capable of delivering in terms of IOPS/bandwidth, but more importantly application elapsed times. And so it was with this customer, a POC where we had to deliver a new platform for their QA system comprised of a large 80-core x86 server and a single 3000 series Violin Memory flash memory array. Full table scans (single-threaded) could drive the array over 1300 MB/s, so the basic plumbing seemed to be in order. Yet having loaded a copy of their production database onto the array and run standard application reports against it, it actually yielded worse results than the production system, an older Solaris box with fewer processors, less RAM (and less SGA/PGA to Oracle), and a spinning-disk based SAN behind it. What the…? In the mix also were lots of small and not-so-small differences: parameter values derived from such physical differences as the core count, the processes setting, the size of the PGA, etc.; the fact that they wanted to test 11.2.0.3 as part of the overall testing (production was still on 11.2.0.1); “system stats” being a term their DBAs had never heard; all kinds of differences in object stats; the list went on. So the new system isn’t keeping up with prod, let alone beating it, you say? Where do I start?

I arrived on site Monday morning with 2 days scheduled to determine the problem and get this engine cranking the kind of horsepower we knew it could. The owner of the POC made it clear his concern was getting maximum performance out of the rig without touching the application code. Standard reports were showing spotty improvements: some were down to 5 minutes from 17 minutes, others were unchanged at 12 minutes, and still others had worsened from 18 minutes to 22 minutes. A batch job that ran 2 hours in production twice a day (more times would be lovely, of course) had run out of TEMP space after 5 hours on the test system. Clearly something was afoot. He had already tried everything I could suggest over email: turning OPTIMIZER_FEATURES_ENABLE back to 11.2.0.1, gathering object stats, gathering workload system stats, trying auto DOP, enabling and then disabling hyper-threading, and more. The only consistent result was an increase in his frustration level.

I asked how he wanted to run this rig, assuming there were no inhibitors. He wanted most of the memory allocated to Oracle, taking advantage of 11.2.0.3’s features and fixes. OK, then let’s set those and start diagnosing from there; no sense fixing a system running in a config you don’t want—especially since efforts to make the test system look and act like prod only with faster storage had all failed. A quick run through of the report test battery showed results similar to what they’d seen before. We broke it down to the smallest granule we could: run a single report, see the SQL it generates on the test system, compare its explain plan there to what production would do with it. This being my first run-in with MicroStrategy reports, I had the fun of discovering every report run generates a “temporary” table with a unique name, inserts its result set into that table, and then returns that result set to the report server. Good luck trending performance of a single SQL ID while making your tuning changes. Well, let’s just compare the SELECT parts for each report’s CTAS and subsequent INSERTs then. What we saw was that the test system was consistently doing more work—a lot more work—to satisfy the same query. More buffer gets, more looping, more complicated plans. Worse, watching it run from the top utility, one oracle process had a single processor at about a trot and was driving unimpressive IO. Here we have this fleet of Porsches to throw at the problem, and we’re leaving all but one parked—and that one we’re driving like we feel guilty for not buying a Prius.

I asked how he wanted to run this rig, assuming there were no inhibitors. He wanted most of the memory allocated to Oracle, taking advantage of 11.2.0.3’s features and fixes. OK, then let’s set those and start diagnosing from there; no sense fixing a system running in a config you don’t want—especially since efforts to make the test system look and act like prod only with faster storage had all failed. A quick run through of the report test battery showed results similar to what they’d seen before. We broke it down to the smallest granule we could: run a single report, see the SQL it generates on the test system, compare its explain plan there to what production would do with it. This being my first run-in with MicroStrategy reports, I had the fun of discovering every report run generates a “temporary” table with a unique name, inserts its result set into that table, and then returns that result set to the report server. Good luck trending performance of a single SQL ID while making your tuning changes. Well, let’s just compare the SELECT parts for each report’s CTAS and subsequent INSERTs then. What we saw was that the test system was consistently doing more work—a lot more work—to satisfy the same query. More buffer gets, more looping, more complicated plans. Worse, watching it run from the top utility, one oracle process had a single processor at about a trot and was driving unimpressive IO. Here we have this fleet of Porsches to throw at the problem, and we’re leaving all but one parked—and that one we’re driving like we feel guilty for not buying a Prius.

New object stats, workload system stats, optimizer features, hyper-threading—all make negligible difference. Histogram bucket counts and values are too close to be a factor. Let’s try hinting some parallelism. BANG. 2 minutes goes down to 15 seconds. Awesome. But we can’t make changes to the code, and certainly not when the SQL is generated by the report server each time. This also means no SQL profiles or baselines. And setting degrees on their tables might open floodgates I don’t want to open. Plus I have DOP set to AUTO. Why isn’t that thing doing anything when it clearly helps the SQL to run in parallel?! Enter the Google.

#MEAT

Ah, the rave reviews of auto DOP. Oh, the ease with which it operates. My, the results you’ll get. But we aren’t getting it. Auto DOP isn’t doing anything for us. How can we make it see parallel execution as a more viable option? Turns out there are several knobs for turning “auto” parallelism up or down, and I was unaware of the combination all them.

Sure there’s your PARALLEL_DEGREE_LIMIT, possibly affected by your core count and PARALLEL_THREADS_PER_CPU, and of course your options for PARALLEL_DEGREE_POLICY, plus PARALLEL_MAX_SERVERS which is derived from some unspecified mix of CPU_COUNT, PARALLEL_THREADS_PER_CPU and the PGA_AGGREGATE_TARGET. But have you run DBMS_RESOURCE_MANAGER.CALIBRATE_IO? Have a look over Automatic Degree of Parallelism in 11.2.0.2 [ID 1269321.1] to see if you might be limiting yourself parallel-wise because the database has no idea what your IO subsystem is capable of. Note that they do not mention workload system stats in this context. I couldn’t find verification that these play no part in DOP, but this note seems to suggest the values in DBA_RSRC_IO_CALIBRATE play a much more significant role now. Following a link about a bug (10180307) in 11.2.0.2 and below, older versions of the CALIBRATE_IO procedure could produce unpredictable results. But more important was the comment that “The per process maximum throughput (MAX_PMBPS) value [might be] too large, resulting in a low DOP while running AutoDOP.” We confirmed this by allowing CALIBRATE_IO to run for about 10 minutes and checking the results. What we saw was 31K IOPS, 328 MB/s total, 334 MB/s per process, and a latency of 0. Interesting numbers, but the explain plan still said the computed DOP was 1. So what does Oracle suggest you do if you don’t like the parallelism? Cheat and set the values manually. According to the same note, start with:

Sure there’s your PARALLEL_DEGREE_LIMIT, possibly affected by your core count and PARALLEL_THREADS_PER_CPU, and of course your options for PARALLEL_DEGREE_POLICY, plus PARALLEL_MAX_SERVERS which is derived from some unspecified mix of CPU_COUNT, PARALLEL_THREADS_PER_CPU and the PGA_AGGREGATE_TARGET. But have you run DBMS_RESOURCE_MANAGER.CALIBRATE_IO? Have a look over Automatic Degree of Parallelism in 11.2.0.2 [ID 1269321.1] to see if you might be limiting yourself parallel-wise because the database has no idea what your IO subsystem is capable of. Note that they do not mention workload system stats in this context. I couldn’t find verification that these play no part in DOP, but this note seems to suggest the values in DBA_RSRC_IO_CALIBRATE play a much more significant role now. Following a link about a bug (10180307) in 11.2.0.2 and below, older versions of the CALIBRATE_IO procedure could produce unpredictable results. But more important was the comment that “The per process maximum throughput (MAX_PMBPS) value [might be] too large, resulting in a low DOP while running AutoDOP.” We confirmed this by allowing CALIBRATE_IO to run for about 10 minutes and checking the results. What we saw was 31K IOPS, 328 MB/s total, 334 MB/s per process, and a latency of 0. Interesting numbers, but the explain plan still said the computed DOP was 1. So what does Oracle suggest you do if you don’t like the parallelism? Cheat and set the values manually. According to the same note, start with:

delete from resource_io_calibrate$;

insert into resource_io_calibrate$ values(current_timestamp, current_timestamp, 0, 0, 200, 0, 0);

commit;

This tells the database a single process can drive at most 200 MB/s from the storage system. If you want more parallelism, tell Oracle each process drives less IO, and the database suggests creating more processes to go after that data. I had already seen a single process driving the array to maximum bandwidth, so ~330 MB/s seemed low, but still it was hindering our parallelism efforts. Even the 200 MB/s setting drove no parallelism in our test. We dropped the value to 50 MB/s and finally parallelism picked itself up off the floor, suggesting a degree of 8. We cranked that puppy down to 5 MB/s and suddenly Oracle wanted to throw all 80 cores at our little query. Booya. We fell back to 50 MB/s, and ran the tests again. We hit a record time of 49s on a report that took 21 minutes in prod. 28 minutes went to 59s for another report. 22 minutes went to 44s. Not everything was <1m. Some only went from 17m to 5m, but this was still enough to make the testers ask if something was wrong. And the 2 hour report that wasn’t finishing in 5 hours completed in 28 minutes.

Maybe you already knew all this, and you’ve loved auto DOP long time. But if you didn’t, I thought I would share my experience in hopes you won’t lose as much time or hair on it. I find potential customers frequently ask whether tuning is required with a flash memory solution, and my honest answer is “sometimes”. This was one of those sometimes.

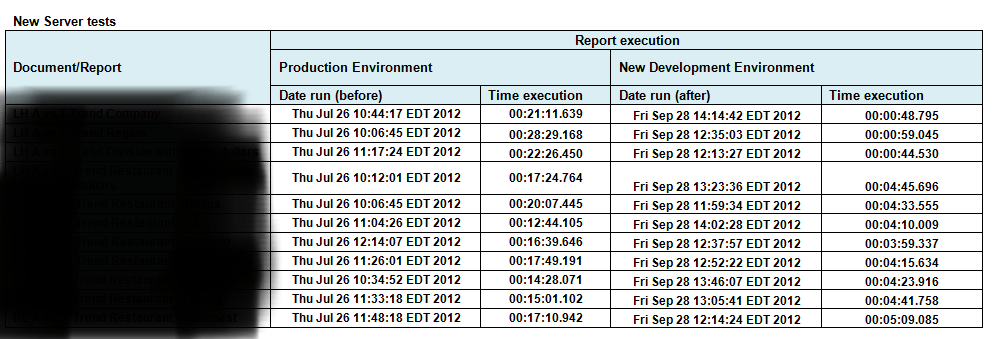

Addendum: Here are the final results from the tuning by Nate – with the report names removed to protect confidentiality:

The Ultimate Guide To Oracle Support

In an effort to provide useful content rather than just blathering on about stuff I’ve written an article on how to work with and understand Oracle Support.

The idea is that if you know the way the organisation works, you can get the best out of your experiences with them. Nothing in the article is confidential, it’s all public domain or located in the myriad support notes on My Oracle Support.

You probably don’t want to know how it works. You certainly don’t need to. Maybe you just drive them, you don’t know how they work. But if you want to understand the processes that drive your service requests click here – it might make the difference:

https://flashdba.com/database/the-ultimate-guide-to-oracle-support/

Why In-Memory Computing Needs Flash

You might be tempted to think that In-Memory technologies and flash are concepts which have no common ground. After all, if you can run everything in memory, why worry about the performance of your storage? However, the truth is very different: In-Memory needs flash to reach its true potential. Here I will discuss why and look at how flash memory systems can both enable In-Memory technologies as well as alleviate some of the need for them.

Note: This is an article I wrote for a different publication recently. The brief was to discuss at a high level the concepts of In-Memory Computing. It doesn’t delve into the level of technical detail I would usually use here – and the article is more Violin marketing-orientated than those I would usually publish on my personal blog, so consider yourself warned… but In-Memory is an interesting subject so I believe the concepts are worth posting about.

In-Memory Computing (IMC) is a high-level term used to describe a number of techniques where data is processed in computer memory in order to achieve better performance. Examples of IMC include In-Memory Databases (which I’ve written about previously here and here), In-Memory Analytics and In-Memory Application Servers, all of which have been named by Gartner as technologies which are being increasingly adopted throughout the enterprise.

To understand why these trends are so significant, consider the volume of data being consumed by enterprises today: in addition to traditional application data, companies have an increasing exposure to – and demand for – data from Gartner’s “Nexus of Forces”: mobile, social, cloud and big data. As more and more data becomes available, competitive advantages can be won or lost through the ability to serve customers, process metrics, analyze trends and compute results. The time taken to convert source data to business-valuable output is the single most important differentiator, with the ultimate (and in my view unattainable – but that’s the subject for another blog post) goal being output that is delivered in real-time.

But with data volumes increasing exponentially, the goal of performance must also be delivered with a solution which is highly scalable. The control of costs is equally important – a competitive advantage can only be gained if the solution adds more value than it subtracts through its total cost of ownership.

How does In-Memory Computing Deliver Faster Performance?

The basic premise of In-Memory Computing is that data processed in memory is faster than data processed using storage. To understand what this means, first consider the basic elements in any computer system: CPU (Central Processing Unit), Memory, Storage and Networking. The CPU is responsible for carrying out instructions, whilst memory and storage are locations where data can be stored and retrieved. Along similar lines, networking devices allow for data to be sent or received from remote destinations.

The basic premise of In-Memory Computing is that data processed in memory is faster than data processed using storage. To understand what this means, first consider the basic elements in any computer system: CPU (Central Processing Unit), Memory, Storage and Networking. The CPU is responsible for carrying out instructions, whilst memory and storage are locations where data can be stored and retrieved. Along similar lines, networking devices allow for data to be sent or received from remote destinations.

Memory is used as a volatile location for storing data, meaning that the data only remains in this location while power is supplied to the memory module. Storage, in contrast, is used as a persistent location for storing data i.e. once written data will remain even if power is interrupted. The question of why these two differing locations are used together in a computer system is the single most important factor to understand about In-Memory Computing: memory is used to drive up processor utilization.

Modern CPUs can perform many billions of instructions per second. However, if data must be stored or retrieved from traditional (i.e. disk) storage this results in a delay known as a “wait”. A modern disk storage system performs an input/output (I/O) operation in a time measured in milliseconds. While this may not initially seem long, when considered in the perspective of the CPU clock cycle where operations are measured in nanoseconds or less, it is clear that time spend waiting on storage will have a significant negative impact on the total time required to complete a task. In effect, the CPU is unable to continue working on the task at hand until the storage system completes the I/O, potentially resulting in periods of inactivity for the CPU. If the CPU is forced to spend time waiting rather than working then it can be considered that the efficiency of the CPU is reduced.

Unlike disk storage, which is based on mechanical rotating magnetic disks, memory consists of semiconductor electronics with no moving parts – and for this reason access times are orders of magnitude faster. Modern computer systems use Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) to store volatile copies of data in a location where they can be accessed with wait times of approximately 100 nanoseconds. The simple conclusion is therefore that memory allows CPUs to spend less time waiting and more time working, which can be considered as an increase in CPU efficiency.

In-Memory Computing techniques seek to extract the maximum advantage out of this conclusion by increasing the efficiency of the CPU to its limit. By removing waits for storage where possible, the CPU can execute instructions and complete tasks with the minimum of time spent waiting on I/O.

While IMC technologies can offer significant performance gains through this efficient use of CPU, the obvious drawback is that data is entirely contained in volatile memory, leading to the potential for data loss in the event of an interruption to power. Two solutions exist to this problem: the acceptance that all data can be lost or the addition of a “persistence layer” where all data changes must be recorded in order that data may be reconstructed in the event of an outage. Since only the latter option guarantees business continuity the reality of most IMC systems is that data must still be written to storage, limiting the potential gains and introducing additional complexity as high availability and disaster recovery solutions are added.

What are the Barriers to Success with In-Memory Computing?

The main barriers to success in IMC are the maturity of IMC technologies, the cost of adoption and the performance impact associated with adding a persistence layer on storage. Gartner reports that IMC-enabling application infrastructure is still relatively expensive, while additional factors such as the complexity of design and implementation, as well as the new challenges associated with high availability and disaster recovery, are limiting adoption. Another significant challenge is the misperception from users that data stored using an In-Memory technology is not safe due to the volatility of DRAM. It must also be considered that as many IMC products are new to the market, many popular BI and data-manipulation tools are yet to add support for their use.

The main barriers to success in IMC are the maturity of IMC technologies, the cost of adoption and the performance impact associated with adding a persistence layer on storage. Gartner reports that IMC-enabling application infrastructure is still relatively expensive, while additional factors such as the complexity of design and implementation, as well as the new challenges associated with high availability and disaster recovery, are limiting adoption. Another significant challenge is the misperception from users that data stored using an In-Memory technology is not safe due to the volatility of DRAM. It must also be considered that as many IMC products are new to the market, many popular BI and data-manipulation tools are yet to add support for their use.

However, as IMC products mature and the demand for performance and scalability increases, Gartner expects the continuing success of the NAND flash industry to be a significant factor in the adoption of IMC as a mainstream solution, with flash memory allowing customers to build IMC systems that are more affordable and have a greater impact.

NAND Flash Allows for New Possibilities

The introduction of NAND flash memory as a storage medium has caused a revolution in the storage industry and is now allowing for new opportunities to be considered in realms such as database and analytics. NAND flash is a persistent form of semiconductor memory which combines the speed of memory with the persistence capabilities of traditional storage. By offering speeds which are orders of magnitude faster than traditional disk systems, Violin Memory flash memory arrays allow for new possibilities. Here are just two examples:

The introduction of NAND flash memory as a storage medium has caused a revolution in the storage industry and is now allowing for new opportunities to be considered in realms such as database and analytics. NAND flash is a persistent form of semiconductor memory which combines the speed of memory with the persistence capabilities of traditional storage. By offering speeds which are orders of magnitude faster than traditional disk systems, Violin Memory flash memory arrays allow for new possibilities. Here are just two examples:

First of all, In-Memory Computing technologies such as In-Memory Databases no longer need to be held back by the performance of the persistence layer. By providing sustained ultra-low latency storage Violin Memory is able to facilitate customers in achieving previously unattainable levels of CPU efficiency when using In-Memory Computing.

Secondly, for customers who are reticent in adopting In-Memory Computing technologies for their business-critical applications, the opportunity now exists to remove the storage bottleneck which initiated the original drive to adopt In-Memory techniques. If IMC is the concept of storing entire sets of data in memory to achieve higher processor utilization, it can be considered equally beneficial to retain the data on the storage layer if that storage can now perform at the speed of flash memory. Violin Memory flash memory arrays are able to harness the full potential of NAND flash memory and allow users of existing non-IMC technologies to experience the same performance benefits without the cost, risk and disruption of adopting an entirely new approach.

More on Exadata X3 “Database In-Memory” (but not by me)

Not a real post – but a recommendation… Kevin Closson, former Performance Architect within Oracle’s Exadata development organisation, has (finally!) written a blog post about the new Exadata X3 model with it’s claimed “Database In-Memory” marketing title.

Not a real post – but a recommendation… Kevin Closson, former Performance Architect within Oracle’s Exadata development organisation, has (finally!) written a blog post about the new Exadata X3 model with it’s claimed “Database In-Memory” marketing title.

For the history of Exadata click here. But more importantly, for the insider view, click here:

Recommended reading…

SLOB using Violin 6616 on Fujitsu Servers

I’ve been too busy to blog recently, which is frustrating because I want to talk more about subjects that are important to me such as Database Virtualization and the great hype around In Memory Databases. However, in the meantime I’d like to share some results from running SLOB (the Silly Little Oracle Benchmark) on Violin Memory flash memory arrays.

I’ve posted some SLOB results in the past, such as these. However, at the time I only had some Nehalem generation CPUs in my lab servers, so I was struggling to generate anything like the level of load that a Violin flash memory array can create.

Now I have some power :-). Thanks to my good friends at Fujitsu I have some powerful servers including an RX300 on which to run some SLOB testing. This is a two-socket machine containing two quad-core Intel Xeon E5-2643 Sandy Bridge processors. Let’s see what it can do.

First let’s run a physical IO test using a Violin Memory 6616 array connected by 8GFC:

Load Profile Per Second Per Transaction

~~~~~~~~~~~~ --------------- ---------------

DB Time(s): 95.9 5,511.9

DB CPU(s): 7.1 406.0

Redo size: 2,729.7 156,939.6

Logical reads: 192,361.2 11,059,614.8

Block changes: 6.0 347.5

Physical reads: 189,430.7 10,891,128.1

Physical writes: 1.9 110.6

Top 5 Timed Foreground Events

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Avg

wait % DB

Event Waits Time(s) (ms) time Wait Class

------------------------------ ------------ ----------- ------ ------ ----------

db file sequential read 119,835,425 50,938 0 84.0 User I/O

latch: cache buffers lru chain 20,051,266 6,221 0 10.3 Other

DB CPU 4,466 7.4

wait list latch free 567,154 572 1 .9 Other

latch: cache buffers chains 1,653 1 0 .0 Concurrenc

The database block size is 8k so that’s 189k random read 8k IOPS. However, as you can see the Oracle AWR report does not calculate the average wait time with enough accuracy for testing flash – the average wait of my random I/O is showing as zero milliseconds. However it’s very simple to recalculate this in microseconds since we just need to take the total time (50,938 seconds) and divide by the total number of waits (119,835,425) then multiply by one million to get the answer: 425 microseconds average latency.

Now let’s run a redo generation test. This time I’m on a Fujitsu PRIMEQUEST 8-socket E7-8830 (Westmere-EX) NUMA box, again connected via 8GFC to the Violin Memory 6616 array. Remember, this test is the one where you create a large enough SGA and buffer cache that the Database Writer does not get posted to flush dirty blocks to disk. As a result, the Log Writer is the only process performing physical I/O. This is a similar workload to that produced during OLTP benchmarks such as TPC-C – a benchmark for which Oracle, Cisco, HP and Fujitsu have all recently used Violin Memory arrays to set records. Here’s the output from my redo SLOB test:

Load Profile Per Second Per Transaction

~~~~~~~~~~~~ --------------- ---------------

DB Time(s): 197.6 2.8

DB CPU(s): 18.8 0.3

Redo size: 1,477,126,876.3 20,568,059.6

Logical reads: 896,951.0 12,489.5

Block changes: 672,039.3 9,357.7

Physical reads: 15,529.0 216.2

Physical writes: 166,099.8 2,312.8

Over 1.4GB/second of sustained redo generation (the snapshot was for a five minute period). That’s an impressive result. Unfortunately I’ve had to sit on it for a month now whilst the details of the Violin and Fujitsu agreement were worked out… but now I am able to share it, I am looking forward to setting some new records using Violin Memory storage and Fujitsu servers. Stay tuned…!

[Update: I confess that in the month or so since I ran these tests I’d forgotten that I didn’t use SLOB to produce the results of the redo test, although it has a perfectly capable redo generation ability… the redo test output above is actually from a TPC-C-like workload generator. The physical read tests are from SLOB though – and it still remains my favourite benchmarking tool!]

In Memory Databases: HANA, Exadata X3 and Flash Memory (Part 2)

In the first part of this blog series on In Memory Databases (IMDBs) I talked about the definition of “memory” and found it surprisingly hard to pin down. There was no doubt that Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM), such as that found in most modern computers, fell into the category of memory whilst disk clearly did not. The medium which caused the problem was NAND flash memory, such as that found in consumer devices like smart phones, tablets and USB sticks or enterprise storage like the flash memory arrays made by my employer Violin Memory.

In the first part of this blog series on In Memory Databases (IMDBs) I talked about the definition of “memory” and found it surprisingly hard to pin down. There was no doubt that Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM), such as that found in most modern computers, fell into the category of memory whilst disk clearly did not. The medium which caused the problem was NAND flash memory, such as that found in consumer devices like smart phones, tablets and USB sticks or enterprise storage like the flash memory arrays made by my employer Violin Memory.

There is no doubt in my mind that flash memory is a type of memory – otherwise we would have to have a good think about the way it was named. My doubts are along different lines: if a database is running on flash memory, can it be described as an IMDB? After all, if the answer is yes then any database running on Violin Memory is an In Memory Database, right?

What Is An In Memory Database?

As always let’s start with the stupid questions. What does an IMDB do that a non-IMDB database does not do? If I install a regular Oracle database (for example) it will have a System Global Area (SGA) and a Program Global Area (PGA), both of which are areas set aside in volatile DRAM in order to contain cached copies of data blocks, SQL cursors and sorting or hashing areas. Surely that’s “in-memory” in anyone’s definition? So what is the difference between that and, for example, Oracle TimesTen or SAP HANA?

Let’s see if the Oracle TimesTen documentation can help us:

“Oracle TimesTen In-Memory Database operates on databases that fit entirely in physical memory”

That’s a good start. So with an IMDB, the whole dataset fits entirely in physical memory. I’m going to take that sentence and call it the first of our fundamental statements about IMDBs:

IMDB Fundamental Requirement #1:

IMDB Fundamental Requirement #1:

In Memory Databases fit entirely in physical memory.

But if I go back to my Oracle database and ensure that all of the data fits into the buffer cache, surely that is now an In Memory Database?

Maybe an IMDB is one which has no physical files? Of course that cannot be true, because memory is (or can be) volatile, so some sort of persistent later is required if the data is to be retained in the event of a power loss. Just like a “normal” database, IMDBs still have to have datafiles and transaction logs located on persistent storage somewhere (both TimesTen and SAP HANA have checkpoint and transaction logs located on filesystems).

So hold on, I’m getting dangerously close to the conclusion that an IMDB is simply a normal DB which cannot grow beyond the size of the chunk of memory it has been allocated. What’s the big deal, why would I want that over say a standard RDBMS?

Why is an In-Memory Database Fast?

Actually that question is not complete, but long questions do not make good section headers. The question really is: why is an In Memory Database faster than a standard database whose dataset is entirely located in memory?

Back to our new friend the Oracle TimesTen documentation, with the perfectly-entitled section “Why is Oracle TimesTen In-Memory Database fast?“:

“Even when a disk-based RDBMS has been configured to hold all of its data in main memory, its performance is hobbled by assumptions of disk-based data residency. These assumptions cannot be easily reversed because they are hard-coded in processing logic, indexing schemes, and data access mechanisms.

TimesTen is designed with the knowledge that data resides in main memory and can take more direct routes to data, reducing the length of the code path and simplifying algorithms and structure.”

This is more like it. So an IMDB is faster than a non-IMDB because there is less code necessary to manipulate data. I can buy into that idea. Let’s call that the second fundamental statement about IMDBs:

IMDB Fundamental Requirement #2:

IMDB Fundamental Requirement #2:

In Memory Databases are fast because they do not have complex code paths for dealing with data located on storage.

I think this is probably a sufficient definition for an IMDB now. So next let’s have a look at the different implementations of “IMDBs” available today and the claims made by the vendors.

Is My Database An In Memory Database?

Any vendor can claim to have a database which runs in memory, but how many can claim that theirs is an In Memory Database? Let’s have a look at some candidates and subject them to analysis against our IMDB fundamentals.

1. Database Running in DRAM – e.g. SAP HANA

I have no experience of Oracle TimesTen but I have been working with SAP HANA recently so I’m picking that as the example. In my opinion, HANA (or NewDB as it was previously known) is a very exciting database product – not especially because of the In Memory claims, but because it was written from the ground up in an effort to ignore previous assumptions of how an RDBMS should work. In contrast, alternative RDBMS such as Oracle, SQL Server and DB/2 have been around for decades and were designed with assumptions which may no longer be true – the obvious one being that storage runs at the speed of disk.

I have no experience of Oracle TimesTen but I have been working with SAP HANA recently so I’m picking that as the example. In my opinion, HANA (or NewDB as it was previously known) is a very exciting database product – not especially because of the In Memory claims, but because it was written from the ground up in an effort to ignore previous assumptions of how an RDBMS should work. In contrast, alternative RDBMS such as Oracle, SQL Server and DB/2 have been around for decades and were designed with assumptions which may no longer be true – the obvious one being that storage runs at the speed of disk.

The HANA database runs entirely in DRAM on Intel x86 processors running SUSE Linux. It has a persistent layer on storage (using a filesystem) for checkpoint and transaction logs, but all data is stored in DRAM along with an additional allocation of memory for hashing, sorting and other work area stuff. There are no code paths intended to decide if a data block is in memory or on disk because all data is in memory. Does HANA meet our definition of an IMDB? Absolutely.

What are the challenges for databases running in DRAM? One of the main ones is scalability. If you impose a restriction that all data must be located in DRAM then the amount of DRAM available is clearly going to be important. Adding more DRAM to a server is far more intrusive than adding more storage, plus servers only have a limited number of locations on the system bus where additional memory can be attached. Price is important, because DRAM is far more expensive than storage media such as disk or flash. High Availability is also a key consideration, because data stored in memory will be lost when the power goes off. Since DRAM cannot be shared amongst servers in the same way as networked storage, any multiple-node high availability solution has to have some sort of cache coherence software in place, which increases the complexity and moves the IMDB away from the goal of IMDB Fundamental #2.

Gong back to HANA, SAP have implemented the ability to scale up (adding more DRAM – despite Larry’s claims to the contrary, you can already buy a 100TB HANA database system from IBM) as well as to scale out by adding multiple nodes to form a cluster. It is going to be fascinating to see how the Oracle vs SAP HANA battle unfolds. At the moment 70% of SAP customers are running on Oracle – I would expect this number to fall significantly over the next few years.

2. Database Running on Flash Memory – e.g. on Violin Memory

Now this could be any database, from Oracle through SQL Server to PostgreSQL. It doesn’t have to be Violin Memory flash either, but this is my blog so I get to choose. The point is that we are talking about a database product which keeps data on storage as well as in memory, therefore requiring more complex code paths to locate and manage that data.

Now this could be any database, from Oracle through SQL Server to PostgreSQL. It doesn’t have to be Violin Memory flash either, but this is my blog so I get to choose. The point is that we are talking about a database product which keeps data on storage as well as in memory, therefore requiring more complex code paths to locate and manage that data.

The use of flash memory means that storage access times are many orders of magnitude faster than disk, resulting in exceptional performance. Take a look at recent server benchmark results and you will see that Cisco, Oracle, IBM, HP and VMware have all been using Violin Memory flash memory arrays to set new records. This is fast stuff. But does a (normal) database running on flash memory meet our fundamental requirements to make it an IMDB?

First there is the idea of whether it is “memory”. As we saw before this is not such a simple question to answer. Some of us (I’m looking at you Kevin) would argue that if you cannot use memory functions to access and manipulate it then it is not memory. Others might argue that flash is a type of memory accessed using storage protocols in order to gain the advantages that come with shared storage, such as redundancy, resilience and high availability.

Luckily the whole question is irrelevant because of our second fundamental requirement, which is that the database software does not have complex code paths for dealing with blocks located on storage. Bingo. So running an Oracle database on flash memory does not make it an In Memory Database, it just makes it a database which runs at the speed of flash memory. That’s no bad thing – the main idea behind the creation of IMDBs was to remove the bottlenecks created by disk, so running at the speed of flash is a massive enhancement (hence those benchmarks). But using our definitions above, Oracle on flash does not equal IMDB.

On the other hand, running HANA or some other IMDB on flash memory clearly has some extra benefits because the checkpoint and transactional logs will be less of a bottleneck if they write data to flash than if they were writing to disk. So in summary, the use of flash is not the key issue, it’s the way the database software is written that makes the difference.

3. Database Accessing Remote DRAM and Flash Memory: Oracle Exadata X3

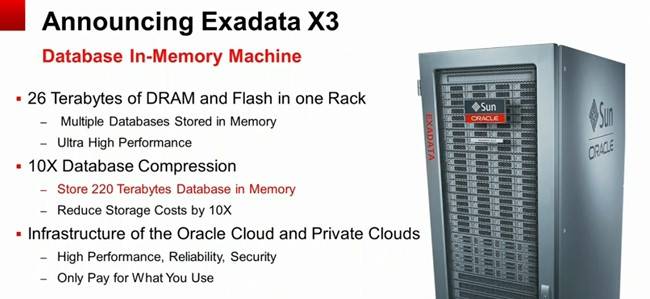

Why am I talking about Oracle Exadata now? Because at the recent Oracle OpenWorld a new version of Exadata was announced, with a new name: the Oracle Exadata X3 Database In-Memory Machine. Regular readers of my blog will know that I like to keep track of Oracle’s rebranding schemes to monitor how the Exadata product is being marketed, and this is yet another significant renaming of the product.

Why am I talking about Oracle Exadata now? Because at the recent Oracle OpenWorld a new version of Exadata was announced, with a new name: the Oracle Exadata X3 Database In-Memory Machine. Regular readers of my blog will know that I like to keep track of Oracle’s rebranding schemes to monitor how the Exadata product is being marketed, and this is yet another significant renaming of the product.

According to the press release, “[Exadata] can store up to hundreds of Terabytes of compressed user data in Flash and RAM memory, virtually eliminating the performance overhead of reads and writes to slow disk drives“. Now that’s a brave claim, although to be fair Oracle is at least acknowledging that this is “Flash and RAM memory”. On the other hand, what’s this about “hundreds of Terabytes of compressed user data”? Here’s the slide from the announcement, with the important bit helpfully highlighted in red (by Oracle not me):

Also note the “26 Terabytes of DRAM and Flash in one Rack” line. Where is that DRAM and Flash? After all, each database server in an Exadata X3-2 has only 128GB DRAM (upgradeable to 256GB) and zero flash. The answer is that it’s on the storage grid, with each storage cell (there are 14 in a full rack) containing 1.6TB flash and 64GB DRAM. But the database servers cannot directly address this as physical memory or block storage. It is remote memory, accessed over Infiniband with all the overhead of IPC, iDB, RDS and Infiniband ZDP. Does this make Exadata X3 an In Memory Database?

I don’t see how it can. The first of our fundamental requirements was that the database should fit entirely in memory. Exadata X3 does not meet this requirement, because data is still stored on disk. The DRAM and Flash in the storage cells are only levels of cache – at no point will you have your entire dataset contained only in the DRAM and Flash*, otherwise it would be pretty pointless paying for the 168 disks in a full rack – even more so because Oracle Exadata Storage Licenses are required on a per disk basis, so if you weren’t using those disks you’d feel pretty hard done by.

[*see comments section below for corrections to this statement]

But let’s forget about that for a minute and turn our attention to the second fundamental requirement, which is that the database is fast because it does not have complex code paths designed to manage data located both in memory or on disk. The press release for Exadata X3 says:

“The Oracle Exadata X3 Database In-Memory Machine implements a mass memory hierarchy that automatically moves all active data into Flash and RAM memory, while keeping less active data on low-cost disks”

This is more complexity… more code paths to handle data, not less. Exadata is managing data based on its usage rate, moving it around in multiple different levels of memory and storage (local DRAM, remote DRAM, remote flash and remote disks). Most of this memory and storage is remote to the database processes representing the end users and thus it incurs network and communication overheads. What’s more, to compound that story, the slide up above is talking about compressed data, so that now has to be uncompressed before being made available to the end user, navigating additional code paths and incurring further overhead. If you then add the even more complicated code associated with Oracle RAC (my feelings on which can be found here) the result is a multi-layered nest of software complexity which stores data in many different places.

Draw your own conclusions, but in my opinion Exadata X3 does not meet either of our requirements to be defined as an In Memory Database.

Conclusion

“In Memory” is a buzzword which can be used to describe a multitude of technologies, some of which fit the description better than others. Flash memory is a type of memory, but it is also still storage – whereas DRAM is memory accessed directly by the CPU. I’m perfectly happy calling flash memory a type of “memory”, even referring to it performing “at the speed of memory” as opposed to the speed of disk, but I cannot stretch to describing databases running on flash as “In Memory Databases”, because I believe that the only In Memory Databases are the ones which have been designed and written to be IMDBs from the ground up.

“In Memory” is a buzzword which can be used to describe a multitude of technologies, some of which fit the description better than others. Flash memory is a type of memory, but it is also still storage – whereas DRAM is memory accessed directly by the CPU. I’m perfectly happy calling flash memory a type of “memory”, even referring to it performing “at the speed of memory” as opposed to the speed of disk, but I cannot stretch to describing databases running on flash as “In Memory Databases”, because I believe that the only In Memory Databases are the ones which have been designed and written to be IMDBs from the ground up.

Anything else is just marketing…

Thoughts on In Memory Databases (Part 1)

Everyone is talking about In Memory at the moment. On blogs, in tweets, in the press, in the Oracle marketing department, in books by SAP employees, even my Violin colleagues… it’s everywhere. What can I possibly add that will be of any value?

Everyone is talking about In Memory at the moment. On blogs, in tweets, in the press, in the Oracle marketing department, in books by SAP employees, even my Violin colleagues… it’s everywhere. What can I possibly add that will be of any value?

Well, how about owning up to something: I find myself in a bit of a quandary on this subject. On the one hand it’s a new buzzword, which means that a) it’s got everyone’s attention, and b) many people with their own agenda will seek to use it to their advantage… but on the other hand, given the nature of my employment (I work for Violin Memory, purveyors of flash memory systems), it seems like something we ought to be talking about.

As anyone who works in the IT industry knows (and perhaps it’s the same in other industries), we love a buzzword. Cloud, Analytics, Big Data, In Memory, Transformation… all of these phrases have been used at one time or another to try and wring cash out of customers who may or may not need the services and products they imagine the phrase represents. Even back at the end of the last millenium consultants worldwide were making huge amounts of money out of exploiting the phrase “Y2K”, some with more honourable intentions than others. I remember my old school received a letter from a “Y2K conformance specialist” informing them that this person could visit and inspect their football pitches to ensure they were “Y2K compliant”… (true story!)

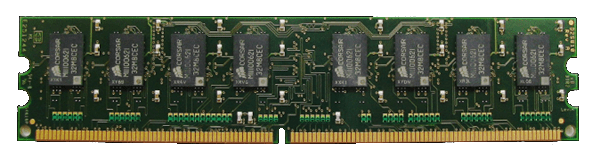

So if buzzwords are prone to misuse, maybe the first thing we need to do is explore what “In Memory” really means? In fact, rewind a step – what do we mean when we say “Memory”?

What Is Memory?

It’s a basic question, but a good definition is surprisingly hard to pin down. Clearly this is an IT blog so (despite the deceiving picture above) I am only interested in talking about computer memory rather than the stuff in my head which stops working after I drink tequila. The definition of this term in the Free Online Dictionary of Computing is:

memory: These days, usually used synonymously with Random Access Memory or Read-Only Memory, but in the general sense it can be any device that can hold data in machine-readable format.

So that’s any device that can hold data in machine-readable format. So far so ambiguous. And of course that is the perfect situation for any would-be freeloader to exploit, since the less well-defined a definition is, the more room there is to manoeuvre any product into position as a candidate for that description.

Here’s what most people think of when they talk about computer memory… DRAM:

This is Dynamic Random Access Memory – and it’s most likely what’s in your laptop, your desktop and your servers. You know all about this stuff – it’s fast, it’s volatile (i.e. the data stored on it is lost when the power goes off) and it’s comparatively expensive to say… disk, for which many orders of magnitude more are available at the same price point.

But now there is a new type of “memory” on the market, NAND flash memory. Actually it’s been around for over 25 years (read this great article for more details) but it is only now that we are seeing it being adopted en mass in data-centres, as well as being prevalent in consumer devices – the chances are your phone contains NAND flash, your tablet (if you have one) and maybe your computer if you are fortunate enough to have an SSD drive in it.

Flash memory, unlike DRAM, is persistent. That means when the power goes, the data remains. Flash access speeds are measured in microseconds – let’s say around 100 microseconds for a single random access. That’s significantly faster than disk, which is measured in (multiple) milliseconds – but still slower than DRAM, for which you would expect an access in around 100 nanoseconds. Flash is available in many forms, from USB devices and SSDs which fit into normal hard drive bays, through PCIe cards which connect direct to the system bus, and on to enterprise-class storage arrays such as those made by my employer like the Violin Memory 6000 series array.

Is flash a type of memory? It certainly fits the dictionary description above. But if you run something on flash, can you describe that something as now running “in memory”? You could argue the point either way I suppose.

Since we don’t seem to be doing well with defining what memory is, let’s change tack and talk about what it definitely isn’t. And that’s simple, because it definitely isn’t disk.

Whether it’s part of the formal definition or not, almost anyone would assume that memory is fast and non-mechanical, i.e. it has no moving parts. It is all semiconductors and silicon, not motors and magnets. A hard disk drive, with its rotating platters and moving actuator arm, is about the most un-memory-like way you can find to store your data, short of putting it on a big reel of tape. And, consistent with our experience of memory versus non-memory devices, it’s slow. In fact, every disk array vendor in the industry stuffs their enterprise disk arrays full of DRAM caches to make up for the slow performance of disk. So memory is something they use to mask the speed of their non-memory-based storage. Hang on then, if you have a small enough dataset so that the majority of your disk reads are coming from your disk array cache, does that mean you are running “in memory” too? No of course not, but the ambiguity is there to be exploited.

Primary Storage versus Secondary Storage

Since we are struggling with a formal definition of memory, perhaps another way to look at it is in terms of primary storage and secondary storage. The main difference here is that primary storage is directly addressable by the CPU, whereas secondary storage is addressed through input/output channels. Is that a good way of distinguishing memory from non-memory? It certainly works with DRAM, which ends up in the primary storage category, as well as disk, which ends up in the secondary storage category. But with flash it is a less successful differentiator.

The first problem is that as previously mentioned flash is available in multiple different forms. PCIe flash cards are directly addressable by the CPU whilst SSDs slot into hard drive bays and are accessed using storage protocols. In fact, just looking at the Violin Memory 6000 series array around which my day job revolves, connectivity options include PCIe direct attached, fibre-channel and Infiniband, meaning it could easily fit into either of the above categories.

What’s more, if you think of primary storage as somehow being faster than secondary storage, the Infiniband connectivity option of the Violin array is only about 50-100 microseconds slower than the PCIe version, yet brings a wealth of additional benefits such as high availability. It’s hard to think of a reason why you would choose the direct attached version of that with Infiniband.

Volatile versus Persistent

Maybe this is a better method of differentiating? Perhaps we can say that memory is that which is volatile, i.e. data stored on it will be lost when power is no longer available. The alternative is persistent storage, where data exists regardless of the power state. Does that make sense?

Not really. Think about your traditional computer, whether it’s a desktop or server. You have four high-level resources: CPU to do the work, network to communicate with the outside world, disk to store your data (the persistence layer). Why do you have memory in the form of DRAM? Why commit extra effort to managing a volatile store of data, much of which is probably duplicated on the persistence layer?

Not really. Think about your traditional computer, whether it’s a desktop or server. You have four high-level resources: CPU to do the work, network to communicate with the outside world, disk to store your data (the persistence layer). Why do you have memory in the form of DRAM? Why commit extra effort to managing a volatile store of data, much of which is probably duplicated on the persistence layer?

DRAM exists to drive up CPU utilisation. Processor speeds have famously doubled every couple of years or so. Network speeds have also increased drastically since the days of the 56k modem I used to struggle with in the 1990’s. Disk hasn’t – nowhere near in fact. Sure, capacity has increased – and speeds have slowly struggled upwards until they reached the limit of the 15k RPM drive, but in comparison to CPU improvements disk has been absolutely stagnant. So your computer is stuffed full of DRAM because, if it weren’t, the processors would spend all their time waiting for I/O instead of doing any work. By keeping as much data in volatile DRAM as possible, the speed of access is increased by around five orders of magnitude, resulting in CPUs which can spend more time working and less time waiting.

In the world of flash memory things are slightly different. DRAM is still necessary to maintain CPU utilisation, because flash is around two-and-a-half to three orders of magnitude slower than DRAM. But does it make sense to assume that “memory” is therefore only applicable to volatile data storage? What if a hypothetical persistent flash medium arrived with DRAM access speeds? Would we refuse to say that something running on this magic new media was running “In Memory”?

In the world of flash memory things are slightly different. DRAM is still necessary to maintain CPU utilisation, because flash is around two-and-a-half to three orders of magnitude slower than DRAM. But does it make sense to assume that “memory” is therefore only applicable to volatile data storage? What if a hypothetical persistent flash medium arrived with DRAM access speeds? Would we refuse to say that something running on this magic new media was running “In Memory”?

I don’t have an answer, only an opinion. My opinion is that memory is solid-state semiconductor-based storage and can be volatile or persistent. DRAM is a type of memory, but not the only type. Flash is a type of memory, while disk clearly is not.

So with that in mind, in the next part of this blog series I’m going to look at In Memory Database technologies and describe what I see as the three different architectures of IMDB that are currently available. As a taster, one of them is SAP HANA, one of them involves Violin Memory and the third one is the new Oracle Exadata X3 “Database In-Memory Machine”. And as a conclusion I will have to make a decision about the quandary I mentioned at the start of this article: should we at Violin claim a piece of the “In Memory” pie?

Using Oracle Preinstall RPM with Red Hat 6

Recently I’ve been building Red Hat 6 systems and struggling to use the Oracle Preinstall RPM because it has a dependency on the Oracle Unbreakable Enterprise Kernel.

I’ve posted an article on this subject and my methods for getting around it: