Storage for DBAs: As a rule of thumb, pretty much any storage system can be characterised by three fundamental properties:

Storage for DBAs: As a rule of thumb, pretty much any storage system can be characterised by three fundamental properties:

Latency is a measurement of delay in a system; so in the case of storage it is the time taken to respond to an I/O request. It’s a term which is frequently misused – more on this later – but when found in the context of a storage system’s data sheet it often means the average latency of a single I/O. Latency figures for disk are usually measured in milliseconds; for flash a more common unit of measurement would be microseconds.

IOPS (which stands for I/Os Per Second) represents the number of individual I/O operations taking place in a second. IOPS figures can be very useful, but only when you know a little bit about the nature of the I/O such as its size and randomicity. If you look at the data sheet for a storage product you will usually see a Max IOPS figure somewhere, with a footnote indicating the I/O size and nature.

Bandwidth (also variously known as throughput) is a measure of data volume over time – in other words, the amount of data that can be pushed or pulled through a system per second. Throughput figures are therefore usually given in units of MB/sec or GB/sec.

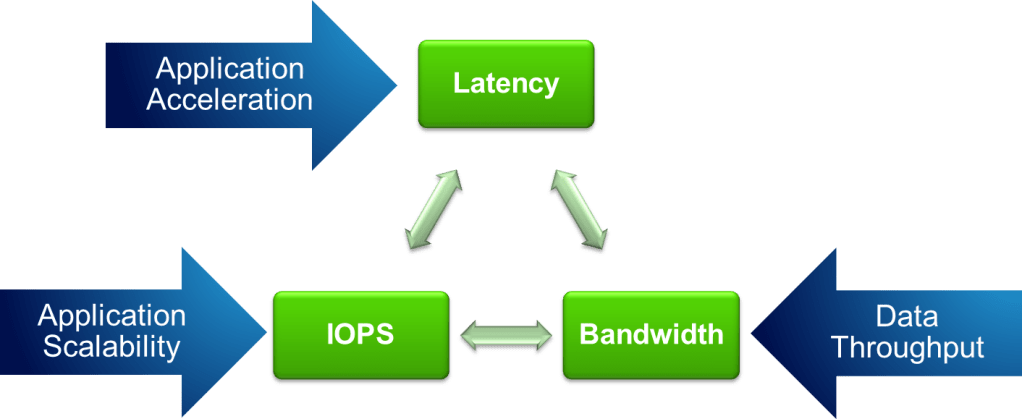

As the picture suggests, these properties are all related. It’s worth understanding how and why, because you will invariably need all three in the real world. It’s no good buying a storage system which can deliver massive numbers of IOPS, for example, if the latency will be terrible as a result.

The throughput is simply a product of the number of IOPS and the I/O size:

Throughput = IOPS x I/O size

So 2,048 IOPS with an 8k blocksize is (2,048 x 8k) = 16,384 kbytes/sec which is a throughput of 16MB/sec.

The latency is also related, although not in such a strict mathematical sense. Simply put, the latency of a storage system will rise as it gets busier. We can measure how busy the system is by looking at either the IOPS or Throughput figures, but throughput unnecessarily introduces the variable of block size so let’s stick with IOPS. We can therefore say that the latency is proportional to the IOPS:

Latency ∝ IOPS

I like the mathematical symbol in that last line because it makes me feel like I’m writing something intelligent, but to be honest it’s not really accurate. The proportional (∝) symbol suggests a direct relationship, but actually the latency of a system usually increases exponentially as it nears saturation point.

We can see this if we plot a graph of latency versus IOPS – a common way of visualising performance characteristics in the storage world. The graph on the right shows the SPC benchmark results for an HP 3PAR disk system (submitted in 2011). See how the response time seems to hit a wall of maximum IOPS? Beyond this point, latency increases rapidly without the number of IOPS increasing. Even though there are only six data points on the graph it’s pretty easy to visualise where the limit of performance for this particular system is.

I said earlier that the term Latency is frequently misused – and just to prove it I misused it myself in the last paragraph. The SPC performance graph is actually plotting response time and not latency. These two terms, along with variations of the phrase I/O wait time, are often used interchangeably when they perhaps should not be.

According to Wikipedia, “Latency is a measure of time delay experienced in a system“. If your database needs, for example, to read a block from disk then that action requires a certain amount of time. The time taken for the action to complete is the response time. If your user session is subsequently waiting for that I/O before it can continue (a blocking wait) then it experiences I/O wait time which Oracle will chalk up to one of the regular wait events such as db file sequential read.

The latency is the amount of time taken until the device is ready to start reading the block, i.e not including the time taken to complete the read. In the disk world this includes things like the seek time (moving the actuator arm to the correct track) and the rotational latency (spinning the platter to the correct sector), both of which are mechanical processes (and therefore slow).

When I first began working for a storage vendor I found the intricacies of the terminology confusing – I suppose it’s no different to people entering the database world for the first time. I began to realise that there is often a language barrier in I.T. as people with different technical specialties use different vocabularies to describe the same underlying phenomena. For example, a storage person might say that the array is experiencing “high latency” while the database admin says that there is “high User I/O wait time“. The OS admin might look at the server statistics and comment on the “high levels of IOWAIT“, yet the poor user trying to use the application is only able to describe it as “slow“.

At the end of the day, it’s the application and its users that matter most, since without them there would be no need for the infrastructure. So with that in mind, let’s finish off this post by attempting to translate the terms above into the language of applications.

Translating Storage Into Application

Earlier we defined the three fundamental characteristics of storage. Now let’s attempt to translate them into the language of applications:

Latency is about application acceleration. If you are looking to improve user experience, if you want screens on your ERP system to refresh quicker, if you want release notes to come out of the warehouse printer faster… latency is critical. It is extremely important for highly transactional (OLTP) applications which require fast response times. Examples include call centre systems, CRM, trading, e-Business etc where real-time data is critical and the high latency of spinning disk has a direct negative impact on revenue.

IOPS is for application scalability. IOPS are required for scaling applications and increasing the workload, which most commonly means one of three things: in the OLTP space, increasing the number of concurrent users; in the data warehouse space increasing the parallelism of batch processes, or in the consolidation / virtualisation space increasing the number of database instances located on a single physical platform (i.e. the density). This last example is becoming ever more important as more and more enterprises consolidate their database estates to save on operational and licensing costs.

Bandwidth / Throughput is effectively the amount of data you can push or pull through your system. Obviously that makes it a critical requirement for batch jobs or datawarehouse-type workloads where massive amounts of data need to be processed in order to aggregate and report, or identify trends. Increased bandwidth allows for batch processes to complete in reduced amounts of time or for Extract Transform Load (ETL) jobs to run faster. And every DBA that ever lived at some point had to deal with a batch process that was taking longer and longer until it started to overrun the window in which it was designed to fit…

Finally, a warning. As with any language there are subtleties and nuances which get lost in translation. The above “translation” is just a rough guide… the real message is to remember that I/O is driven by applications. Data sheets tell you the maximum performance of a product in ideal conditions, but the reality is that your applications are unique to your organisation so only you will know what they need. If you can understand what your I/O patterns look like using the three terms above, you are halfway to knowing what the best storage solution is for you…

These are my thoughts and ideas – I’m not claiming them as facts. The data here is not real – it is my attempt at visualising my opinions based on experience and interaction with customers. I’m quite happy to argue my points and concede them in the face of contrary evidence. Of course I’d prefer to substantiate them with proof, but until I (or someone else) can devise a way of doing that, this is all I have. Feel free to add your voice one way or the other… and yes, I am aware that I suck at graphics.

These are my thoughts and ideas – I’m not claiming them as facts. The data here is not real – it is my attempt at visualising my opinions based on experience and interaction with customers. I’m quite happy to argue my points and concede them in the face of contrary evidence. Of course I’d prefer to substantiate them with proof, but until I (or someone else) can devise a way of doing that, this is all I have. Feel free to add your voice one way or the other… and yes, I am aware that I suck at graphics.

The basic premise of In-Memory Computing is that data processed in memory is faster than data processed using storage. To understand what this means, first consider the basic elements in any computer system: CPU (Central Processing Unit), Memory, Storage and Networking. The CPU is responsible for carrying out instructions, whilst memory and storage are locations where data can be stored and retrieved. Along similar lines, networking devices allow for data to be sent or received from remote destinations.

The basic premise of In-Memory Computing is that data processed in memory is faster than data processed using storage. To understand what this means, first consider the basic elements in any computer system: CPU (Central Processing Unit), Memory, Storage and Networking. The CPU is responsible for carrying out instructions, whilst memory and storage are locations where data can be stored and retrieved. Along similar lines, networking devices allow for data to be sent or received from remote destinations. The main barriers to success in IMC are the maturity of IMC technologies, the cost of adoption and the performance impact associated with adding a persistence layer on storage. Gartner reports that IMC-enabling application infrastructure is still relatively expensive, while additional factors such as the complexity of design and implementation, as well as the new challenges associated with high availability and disaster recovery, are limiting adoption. Another significant challenge is the misperception from users that data stored using an In-Memory technology is not safe due to the volatility of DRAM. It must also be considered that as many IMC products are new to the market, many popular BI and data-manipulation tools are yet to add support for their use.

The main barriers to success in IMC are the maturity of IMC technologies, the cost of adoption and the performance impact associated with adding a persistence layer on storage. Gartner reports that IMC-enabling application infrastructure is still relatively expensive, while additional factors such as the complexity of design and implementation, as well as the new challenges associated with high availability and disaster recovery, are limiting adoption. Another significant challenge is the misperception from users that data stored using an In-Memory technology is not safe due to the volatility of DRAM. It must also be considered that as many IMC products are new to the market, many popular BI and data-manipulation tools are yet to add support for their use. The introduction of

The introduction of